Here is a sample that showcases why we are one of the world’s leading academic writing firms. This assignment was created by one of our expert academic writers and demonstrated the highest academic quality. Place your order today to achieve academic greatness.

There is very little knowledge held by the public or academic scholars about chauffeurs working in metropolitan areas like London. Preliminary literature review on the subject reveals that there are very few scholarly studies on the topic that may include opinions or conclusions about the subject from the perspective of drivers that work in the industry.

There are blogs from industry related websites that may provide very little insight into the experiences of luxury or corporate chauffeurs. A greater part of the literature focuses on the transportation industry’s organizational structures, regulation, and supply and demand relationship.

Studies like Blasi and Leavitt (2006) concentrate on measuring drivers’ performance through specific indicators like promptness to respond to calls and safety. The automobile is considered man’s greatest and unique invention devised to ease the movement of people, equipment and commodities. The advent of the first Model T by Ford motors in the 1920s has led to increased models, makes, and designs of automobiles by various companies.

This increase in different automobiles is resultant from the improvements made on the machinery to improve safety, efficiency, and comfort for users who may be private or corporate customers.

Regardless of the major improvements made on motorcars to make them more user friendly, automobile users still experience health problems associated with using automobiles (Brinchmann, et al., 1987).

Major problems include lower back pain (LBP) and other musculoskeletal disorders (MSD). Driving motorcars especially those in private transportation industry face an occupation that require serious tedious tasks with a high level of responsibility for the car operator.

There are many underlying causes and risks associated with public driving that been studies and reported widely as being at an increased risk of lower back pain, whole body vibrations and excessive fatigue (Biering-Sorensen, 1984).

The current report examines the various ergonomic issues experienced by drivers within the private car service industry by analysing the Lexus ES 250 Model 2018 workstation.

According to Darby et al. (2010) a workstation is defined as an area with equipment that an individual use to conduct tasks or a specific job. The current study examines the technical use of the vehicle by drivers to transport clients to and from sites.

Vehicle ergonomic research has found that prolonged periods of sitting can place heavy demands on an individual’s posture, specifically when sitting in a vehicle caused by the added impact of movement and vibration on the body.

Many studies have pointed out that common risks associated with driving includes MSD’s, fatigue, vibration, and sun exposure (Byrns et al., 2012).

The current study analyses 25 different drivers assigned to the Lexus ES 250 Model 2018 workstation under a private luxury chauffeur service in London.

The participants in the ergonomic study were asked to respond to interview questions and a questionnaire with regards to work related stressors that may impact their physical selves and ability to continue working.

The primary aim of the current study is to use ergonomic research techniques to assess the workstation of luxury chauffeurs, specifically using the Lexus ES 250 Model 2018.

The study aims to effectively implement ergonomic research methods to better understand the physical constraints that impact luxury car service drivers. To achieve the aim, the following objectives have been developed.

The developed objectives of the research will enable the researcher to achieve the aim and purpose of the study. Furthermore, the objectives will act as guidelines to ensure that the study is conducted thoroughly and provides the appropriate insight.

Various studies have identified the ergonomic risks known to potentially cause fatigue and occupational stressors responsible for numerous uncomfortable experiences by drivers of saloon parlour cars. Some of the most predominant occupational stressors while driving are postural stress (PS), whole body vibrations, lower back pains (LBP), musculoskeletal disorder, and fatigue. Byrns et al. (2002) noted that occupational lower back pain has become a major cause of morbidity and cost to many drivers.

Byrns et al. (2002) also noticed that efforts to control lower back pain have been very unsuccessful, leading to improved understanding of the risks associated with it and added psychological factors that may come about it.

A study conducted by Funakoshi et al. (2003) on LBP and working conditions among men taxi drivers revealed that the drivers’ seat contributed to the experience of whole body vibrations and job stress leading to drivers developing lower back pain.

A second study conducted by Funakoshi et al. (2004) had measured whole body vibrations on the divers’ seat pan of 12 drivers under their actual working conditions.

The results of Funakoshi et al. (2004) study were evaluated based on the health guidelines of international standards, specifically the ISO 2631-1:1997; it was found that the majority of frequency weighted R.M.S accelerations of the cabs fell into the category of ‘potential health risks’ under the specifications of the standard used.

According to Okuribidio et al. (2007) there is an increasing interest in ergonomic principles into the design of motor vehicle interiors is a recent development in the academic and industrial fields.

Okuribidio et al. (2007) also found an increased need to introduce ergonomic concepts into industrial products that consider consumers’ requests and expectations. Since the 1960s major car manufacturers have created laboratories and bodies concerned with ergonomics have been quite active.

Academics agree that it has become imperative to incorporate ergonomic principles right at the start of a product’s design stage. However, over time, there are possibilities that reasonable changes can be made and inevitable by being done so with more ease.

Funakoshi et al. (2004) suggests that it is important to develop a porotype to test ergonomic verifications to make significant changes without it there is a greater possibility of generating high costs in the event of interventions.

Studies have found that work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMD) and other types of postural damage may result in physiological sicknesses that may come from lengthy mechanical stresses felt on the musculoskeletal system of the human body (Onawumi et al., 2012).

The phenomena of experiencing WRMDs are prevalent worldwide amongst individuals who engage in occupational driving, best studied under taxi cab drivers. This experience is often attributed to the poor design of drivers’ workplace and poor sitting posture being the leading causes of stresses and strains experienced by drivers.

Blasi and Leavitt (2006) has recorded in their study that driving public transport vehicles frequently causes the long term adoption of cramped postures and whole body vibrations.

Blasi and Leavitt (2006) have also found that back pain problems in driving are known to be caused by constrained work postures and vibrations induced fatigue on tendons and muscles of drivers. Academics have also found a need to integrate both the operator’s capabilities and automobile performance requirements sufficiently to reduce the occupational hazards – both known and unknown- to which drivers may be often subjected to.

Onawumi et al. (2012) have found that the persistent exposure to risks such as LBP, discomfort, and stress are all caused by unfit workplaces in which drivers are confined, resulting in fatal accidents leading to the vehicle lives and properties that may be in it.

Hence, it has become imperative to study cumulative trauma disorder and other stress-induced problems that may effectively reduce drivers’ fatigue and enhance the drivers’ performance and safety.

Funakoshi et al. (2004) suggest a need to study the interaction between “anthropometric characteristics of human body, the biomechanical properties, and physical dimensions” of the workplace.

Academics have recommended surveying and compiling anthropometric data of the various operators in the UK to specify apposite vehicles that should be allowed into the country for purposes of public transport like taxis and luxury car services.

Blasi and Leavitt (2006) report that major causes of motor accidents are human factors with characteristics attributed to operators’ physical, anatomical, physiological, and psychological peculiarities using vehicles.

Human body characteristics need to be considered in the design of motor vehicle interiors to enhance productivity, comfort, safety, and performance at work for drivers.

The United Kingdom is recognised as the fourth largest importer of cars in the world in 2017, with imports worth 44.1 billion USD which composes 5.9% of the market share in the world which can be considered a potential contributor of risks that may be experienced by taxi cab operators and luxury car service operators.

These risks may be associated with design errors resulting from anthropometric dimensions of populations whose body measurements may not include the typical Briton. There are a few legislative controls on the types and conditions of imported vehicles, lack of effective enforcement.

In cases for countries where there are no anthropometric databases to assist automobile manufacturers in designing user-friendly cars individuals are then forced to fit into non-fitted technological systems due to their availability in the market.

In common cases of body pains and other musculoskeletal disorders can be minimised if government agencies responsible for consumer protection ensure that required data is collected and used by local and foreign automobile companies.

Orders completed by our expert writers are

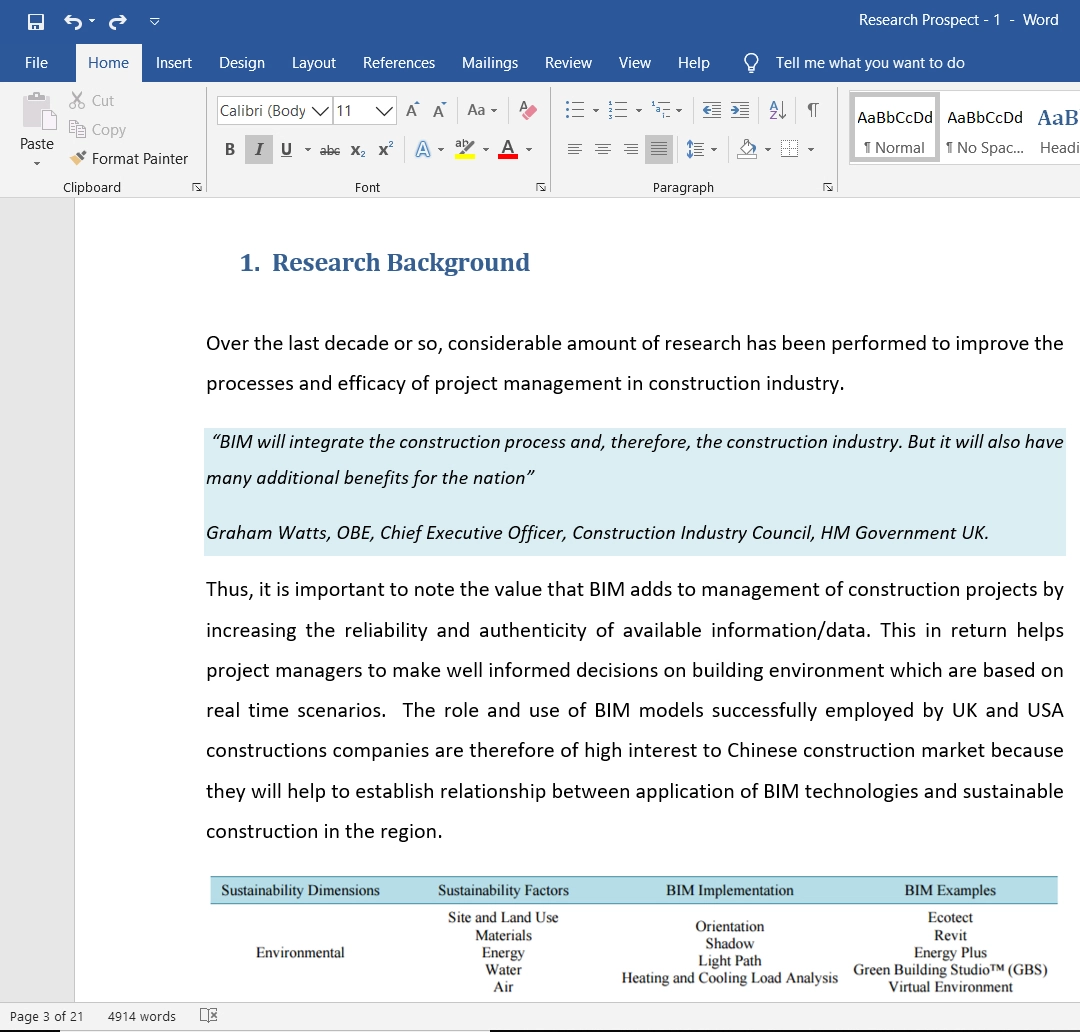

The current study asked respondents to indicate the number of hours they worked by luxury car service drivers. The median working hours of the 25 participants were then tabulated and are displayed before.

Table 1- Median Work Week of Participants in Hours

| Non-airport per days worked | 14 |

| Airport hours per day worked | 16 |

| Days worked per Week | 6 |

| Total hours worked per Month | 370 |

The median luxury car service driver in London works on average 370 hours per month, with typical drivers working 85 hours per week. Commonly drivers are said to work more than 12 hours per day, often seven days per week. When asked, drivers indicated that they either have zero to one day off in the last 30days of working. Academics such as Blasi and Leavitt (2006) have reported that drivers make more money on longer fares that are picked up at the airport with drivers working even longer hours, a median of 14 hours, on days air-port fares are reserved.

Participants were also asked to indicate their general health status on the questionnaire. Drivers who participated in the current study were asked to indicate their general health status based on self-assessed terms. The figure below illustrates the self-described health status of the drivers of luxury saloon cars. According to most drivers of Lexus ES 350 2018 in the current study had “fair” health about 40%.

Figure 1- Self-described health status of Participant drivers

Generic health problems were also examined in the questionnaire using participant responses. These responses indicated health problems that have been medically diagnosed by general health practitioners and various academic literature that associates several illnesses with drivers.

Table 2- Generic Health Issues of Drivers from GP Diagnosis

| Health Problems | Current Study Drivers’ Reporting | Previous Academic Literature Driver Reporting* |

|---|---|---|

| Back pain severe enough to interfere with daily activities | 50% | 49% |

| Problems in leg, swollen legs, or left leg limp | 10% | 40% |

| Shoulder Pain severe enough to interfere with daily activities. | 10% | 30% |

| Vision Issues | 0% | 34% |

| High Blood Pressure | 15% | 24% |

| Excessive Weight Gain or Obesity | 15% | 21% |

* The data is derived from reported data taken from (Blasi and Leavitt, 2006).

The table 2 indicates that the current study’s 50 per cent of respondents indicated that they have been diagnosed with severe back pain that enables or interferes with their daily activity.

This percentage is close to the percentage status of Blasi and Leavitt (2006) who indicated in their study that 49% of their 283 respondents indicated diagnoses of back pain.

Problems in the leg, swollen legs, or left limp account for 10% of the respondents being diagnosed. On the other hand, the Blasi and Leavitt (2006) study presented that 40% of their respondents indicated some form of the stated leg pain was experienced.

In the current study shoulder pain severe enough to interfere with daily activities accounted for ten per cent of participant diagnosed health issues.

In comparison, previous academic studies accounted it for 30 per cent. The current study’s participants did not present any form of eye or vision problem but other academics studies indicated that 34 per cent of its participants had faced this health concern.

High blood pressure in the current demographic accounted for 15 per cent while other studies indicated that 24 per cent of their respondents had faced high blood pressure diagnosis.

Lastly, 15 per cent of the current respondents indicated excessive weight gain or obesity while 21 per cent of respondents from other studies indicated this health issue.

Studies have suggested that posture is not the only reason for the issue of back pains, road vibrations are also known to aggravate back health issues.

Studies such as Blasi and Leavitt (2006) have suggested that required and controversial partitions between the passenger and the driver seat are known to intensify back problems in drivers, especially for taller drivers.

Drivers such as participant D in the current study indicated in their interview that “industry average for passengers being present in the car is 17 minutes, however, I am in the car for over 17 hours at a time making it very necessary for me to stay comfortable”.

Participant A in the interview portion of the study described the sufferings that are common for taller drivers like themselves,

“There are some drivers like myself who have very long legs and it makes it difficult to sit straight or even relax. Many of my colleagues who are also drivers have complained of back pains as they are not able to adjust the seats of the car to the fullest extent; while customers complain of being squeezed in so tight”.

Drivers also reported of a specific pain that appeared over excessive driving particularly in the right leg as so much of their working time it is used to control the clutch and accelerator, while the left leg is used for brakes. Blasi and Leavitt (2006) had termed this as the “taxi driver limp” because of the excessive use of one leg for long periods of time.

Table 3- Cab Fit Comparison (Median measurements of participants)

| Vehicle Dimensions | cm | Driver Anthropometric Dimensions | cm | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seat pan height at front | 36 | Popliteal (back of knee) height | 35.56 | |

| Seat pan depth | 50 | Buttocks to popliteal length | 45.72 | |

| Seat pan width | 43.56 | Hip breadth | 37 | |

| Back rest height | 45.72 | Sitting shoulder height | 46 | |

| Head rest height | 15.24 | Sitting height | 82.1 | |

| Top centre of seat back to top of steering wheel | 61 | Forward grip reach | 55.88 | |

| Steering wheel thickness | 4 | Hand length | 19.05 | |

| Seat pan to steering wheel | 25.4 | Thigh thickness | 45.72 | |

| Top of right shoulder to hand control on the right hand side of the seat | 66 | Forward grip reach- right | 70 | |

| Top of left shoulder to hand control on the right hand side of the seat | 66 | Forward grip reach- left | 70 | |

| Height of door aperture | 81.28 | Seating height | 82.1 | |

| Width of door aperture | 91.44 | Highest value of body breadth and body width |

The drivers were assessed on several of their work related journey with pictures and videos being made to allow for an analysis to take place for driver posture and limb movements using RULA method.

The results of the RULA analysis are displayed for one of the drivers that agreed to participate in this investigation. The action level 2 indicated on the table implies that further investigation is needed and changes made need to be made.

Table 4- RULA Findings of Participant

| Activity | Score | Action Level |

|---|---|---|

| Controlling steering while driving on road. | 4 | 2 |

| Reversing vehicle | 4 | 2 |

| Pulling out from rest position | 3 | 2 |

| Operating gear lever | 3 | 2 |

| Operating hand brake | 3 | 2 |

Biering-Sorensen, F. 1984. Physical measurement as a risk indicator for low-back trouble over one-year period. Spine. 9(2), 106-119.

Blasi, G., and Leavitt, J. 2006. Driving poor: Taxi drivers and the regulation of the taxi industry in Los Angeles. [report] UCLA Institution of Labor and Employment.

Brinchmann, P., Johannleweling, N., Kilweg, D., and Biggerman, M. 1987. Fatigue fracture of human lumbar vertebrae. Clinical Biomechanics, 34, pp. 909-918.

Byrns, G., Agnew, J., Curbow, B., 2002. Attributions, stress, and work-related low back pain. Applied Occupation Environment Hygiene, 17(11), pp. 752 – 764.

Darby, A. M., Pitts, P., Heaton, R., and Mole, M. 2010. Whole-body vibration and ergonomics of driving occupations – Ports industry. Health and Safety Executive [Report], Report No. RR767. Accessed 30 June 2018 < http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr767.pdf >.

Funakoshi, M., Tamura, A., Taoda, K., Tsujimura, H., and Nishiyama, K. 2003. Risk factors for low back pain among taxi drivers in Japan. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi, 45(6), pp. 235-247.

Funakoshi, M., Tamura, A., Taoda, K., Tsujimura, H., and Nishiyama, K. 2004. Measurement of whole-body vibration in tax drivers. Applied Ergonomics, 46(2), pp. 119-124.

Onawumi, A. S. Lucas, E. B., Abebiyi, K. A. 2012. Ergonomic assessment of driver’s seat of taxicabs used in Nigeria. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Technology, 2(1), pp. 1-16.

Okuribidio, O. O., Shimble, S. J., Magnusson, M., and Pope, M. 2007. City bus driving and low back pain: A study of the exposures to posture demands manual materials handling and whole body vibration. Applied Ergonomics, 38(1), pp. 29-38.

To write a master’s level academic report: