Here is a sample that showcases why we are one of the world’s leading academic writing firms. This assignment was created by one of our expert academic writers and demonstrated the highest academic quality. Place your order today to achieve academic greatness.

The current Greek government debt crisis, also known as the Greek depression, was a major international political event in the European Union.

The crisis occurred in late 2009, making it the first of the five ‘sovereign debt crises’ within the Eurozone. Other sovereign states that comprised the European debt crisis included Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus.

The economy of Greece is the 45th largest globally based on the nominal gross domestic product (GDP), producing on average $238 billion per year.

Furthermore, it is the 51st largest economy based on purchasing power parity, with an average of $86 billion per year (EU, 2015). By 2013, Greece had the thirteenth largest economy within the 28 member states of the European Union.

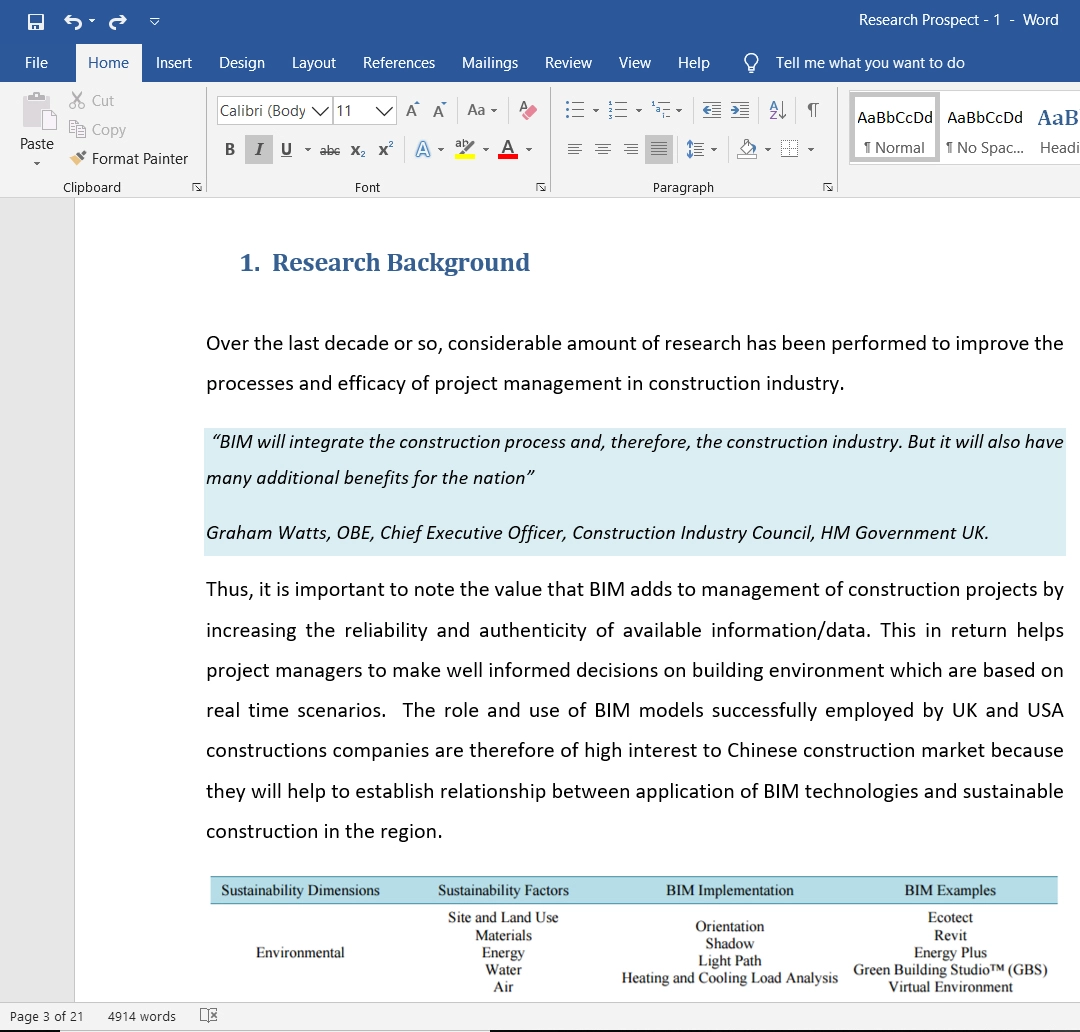

The Greek economy fits into a developed country’s category with their economy based mostly on the service sector. To break this down, Greece’s economy is divided as follows with its percentage contribution to the national economic output as approximated in 2012:

The most important of Greece’s industries are tourism and shipping. This is apparent as, by 2013, Greece had recorded about 18 million international tourists.

According to UNWTO (2013), Greece was the 7th most visited country in the European Union and the 16th most visited country. Greece’s economy has seen many ups and downs, beginning with World War II, which devastated it; however, it recovered in the 1950-1980 Greek economic miracle (Allison and Nicolaidis, 2012).

High GDP growth levels followed this in Greece, which was considered above the Eurozone average. However, the country made another downward spiral with the Great Recession and subsequent Greek government-debt crisis.

This research will uncover the various causes of Greece’s recent debt crisis and its consequent effects on the Greek economy.

Therefore, the current study’s primary focus is to understand the impact of factors on the Greek population in terms of unemployment, government welfare programs, consumer spending power, and other socio-economic impacts. The details of the research aim and objectives of the current study have been described in length below;

The research aims of the current study are:

Address the research questions: What are the socio-economic impacts of the Greek government’s debt crisis on Greece’s citizens? What has caused these socio-economic implications and the current debt crisis?

Develop an understanding of how the Great Recession influenced the resulting debt crisis and how the Greek government influenced its economy to be led into such a crisis.

Investigate major economic decisions that produced economic instability in Greece. There is a need to highlight the various major decisions the Greek government took, especially its statistical credibility since Greece applied for Euro membership in 1999.

Investigate the economic impact that has been made since the debt crisis began in regards to the country’s local economy, the international economy, and particularly that of the Eurozone.

Identify the major stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities within the Greek economy, particularly towards the stakeholders’ take on economic policies and programs.

Analyse the efficacy of current economic strategies that have been implemented, product recommendations based on those strategies to improve economic gain, and ensure that the current crisis is not repeated.

The research objectives are;

Review economic trends of the Greek economy in terms of the economic and business cycle. This will reveal the current and historical performance of the economy. Data will be obtained from various sources such as the IMF database, World Bank database, and Eurostat.

Explore economic concerns linked to Greece’s GDP growth rates, government deficit, government debt level, budget compliance, and statistical credibility.

Based on these factors, a link will be made to macro-and micro- economy changes that impacted Greece’s citizens.

Review the current practices and policies that have been established to minimize the limit or reduce the negative effects on the economy.

This research aims to determine the socio-economic effects of the Greek crisis on the citizens of Greece. The study looks to produce evidence-based recommendations and suggestions to improve its economy and prevent this crisis from occurring again. Therefore, the concerned research question of the current study is:

What are the social and economic implications of the Greek government debt crisis on the residents/citizens of Greece?

Throughout the study, the question will be addressed, particularly when providing recommendations for improving the economy to return to a stable position.

Greece’s economy evolved for most of the 19th century due to the Industrial Revolution’s upsurge, a contributing era that transformed a great deal of the world.

There was a gradual and steady development of the industry and further shipping development in Greece, which was once dominated by an agricultural economy. Between 1833 and 1911, Greece’s average per capita GDP growth rate was lower than other Western European nations (Kostis and Petmezas, 2006).

There was a surge in industrial activity, but this was limited to heavy industry such as ship-building, mainly in Greece’s Ermoupolis and Piraeus (Kostis and Petmezas, 2006; Skartsis, 2012).

However, even with the industry’s new strength to power the economy, Greece faced economic hardships and defaulted on external loans in 1826, 1843, 1860, and 1894. During this time, the standard of living in Greece mirrored the economic trend of the times.

According to Bairoch (1976), the per capita income using the indicator of purchasing power of Greece in comparison to France was 68% of France in 1850: 56%, in 1880: 62%, 1938: 75%, in 1980: 90%, in 2007 and 96.4% in 2008.

After World War II, Greece’s development is linked to the Greek economic miracle, which witnessed growth rates compared with that ofJapan. During this time, Greece ranked first in Europe in terms of GDP growth.

Allison and Nicolaidis (2012) assert that between 1960 and 1973, Greece’s economy grew by an average of 7.7% compared to 4.7% for the remaining EU-15 countries, and 4.9% that was present in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Allison and Nicolaidis (2012) also report that exports during 1960 and 1973 grew at an average rate of 12.6 % a year.

The Greek economy is supported significantly by the service sector, particularly by its shipping industry and tourism. The Greek Merchant Navy is the largest globally, with Greek-owned vessels comprising 15 percent of the global deadweight tonnage as of 2013 (Eurostat, 2015).

Greece’s shipping industry boomed due to the increased demand for international maritime trade between Greece and Asian countries, which led to an increase in investment into the shipping industry.

Shipping has remained a traditional and critical sector player in the Greek economy from ancient times. However, Greece is also a significant agricultural producer in the EU.

The country has been a significant legatee of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union since it entered the EU, allowing for Greece’s agricultural infrastructure to be upgraded and output, thus increasing (Eurostat, 2015).

This resulted in an 885% increase in organic farming in Greece between 2000 and 2007. It is considered the highest percentage change in all of the EU (Eurostat, 2015)

Since Greece is a large economy situated in the Balkans, it has become a regional investor. The country has become a large foreign investor of capital in Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Macedonia. Between 1997 and 2009, Greece contributed 12.11 percent of foreign direct investment capital in the Republic of Macedonia (Eurostat, 2015).

Solely analyzing the year 2009, Greece invested 380 million euros in the Republic of Macedonia using companies such as Hellenic Petroleum to make imperative strategic investments (Eurostat, 2015).

As 2009 was closing, the Greek economy faced its most severe economic crisis since 1974, caused by various combinations of local and international factors. The government revised its deficit from the predicted 3.7 percent in early 2009 to 6 percent in September 2009 and a GDP of 12.7 percent.

Unfortunately, Greece has become the most shaken epicentre of the consolidated European debt crisis since the implosion of Wall Street in 2008.

While many of the global financial markets were reeling from the implosion, Greece announced in October of 2009 that it had been understating its deficit figures for many years, which led many to question the soundness of Greece’s finances.

This led to the country being shut out of further borrowing in the financial markets. From April to May 2010, the country headed towards bankruptcy, threatening to set off a new financial crisis.

The masking of real deficit and debt levels resulted from the Maastricht Treaty, signed in 1992. Under the treaty, member states of the EU pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels.

Nonetheless, by the early 2000s, a few EU member states, including Greece, failed to operate within limits set by the Maastricht requirements and instead began to securitize future government revenues to decrease their debts and deficits.

This allowed the sovereign states’ such as Greece, to hide their deficit and debt levels through various techniques such as inconsistent accounting, off-balance-sheet transactions, and the use of complex currency and credit derivative structures.

However, in 2009, Greece’s newly elected government stopped hiding the country’s true indebtedness and budget deficit.

The under-reporting of figures came to light after three revisions of the 2009 budget deficit forecast what was proclaimed as being from 6-8% of GDP; the Maastricht Treaty asks for no greater than 3 percent of GDP, and this was changed to 12.7% after Pasok won the 2009 October national elections.

The low forecast of 6-8% was reported around September 2009 and did not correspond with the situation. In actuality, Greece had a debt that exceeded $-400 billion, over 120% of GDP, with France owning 10 percent of the debt.

Figure 2- Debt Profile of Eurozone countries (Source; The Lisbon Council, 2011)

The beginning of 2010 brought anxiety and tension due to excessive national debt as lenders began to demand higher interest rates from Greece who had higher debt levels, deficits, and current account deficits.

This made it difficult for the Greek government to finance more budget deficits and repay or even attempt to refinance existing government debt, especially since the country’s economic growth rate was low. A large percentage of debt was in the control of foreign creditors.

Orders completed by our expert writers are

The European Union’s economy is considered heterogeneous, with policies that vary tremendously from country to country, resulting in outcomes that differ depending on each country. However, despite the diversity in economies, specific, vivid patterns separate strong economies from weaker ones or equally strong and weak ones.

For example, Sweden is considered the EU’s best-managed economy and the worst (Economic Commission, 2015). The Swedish economy holds strong finances, but its overall growth has seen a downward spiral since 2009, as export demand and consumption have fallen (Economic Commission, 2015).

Greece and Spain, however, have shown abstruse performance by doing well in some years and cataclysmically badly in others.

The EU-15 witnessed robust economic growth between the end of World War II and the 1970s. At the time, the consolidated gross domestic product per capita had increased by over 70 percent in EU-15 countries, compared to less than 50 percent in 1945 (OECD, 2011).

Unfortunately, by 2007, the GDP per capita in EU countries had fallen to 68 percent, with a great deal of Greece. According to the OECD (2011), the decrease in GDP per capita of EU states is caused by persistently lower productivity, lower employment, and less human capital, as Europe only surpasses developed countries like the United States in physical capital.

The wide gap between the EU-15 and the USA is attributed to the interaction between macroeconomic shocks in the 1970s and 1980s and the labour market institutions present in Europe, causing a rise in the unemployment rate (Blanchard and Wolfers, 2000).

However, Ark et al. (2008) assert that differences between the E-15 and the US can be explained by greater adoption of information and communication technologies and more rapid productivity in the EU-15 and the US.

Figure 3- GDP per capita in EU-15 (1950-2012) (Source; Balcerowicz, 2013)

The overall picture obtained from the analysis of the period 1980-2007 is also important for showing differences among the EU-15 countries. Different countries were known to display different growth performances during 1980-2007, with each of the EU-15 countries displaying different growth rates over time.

Each of the 15 countries can be categorized using ‘growth episodes’ divided between accelerations and slowdowns, as seen in Table 1. Each country that is either seeing an acceleration or deceleration is affected by factors of changes in systematic forces generally changing the institutional framework; the fiscal stance; the age structure of the population; and strong shocks, with persistent and strong accelerations of public and private spending driven by strong capital inflows and excessive growth of credit (Balcerowicz, 2013).

Balcerowicz (2013) defined slowdowns as periods when the GDP per capita in a given country grew one percentage point slower than in the US for five years consecutively or longer.

On the other hand, Balcerowicz (2013) describes accelerations as the periods when GDP per capita in a given country grew 0.5 percentage points faster than in the US for five years consecutively or longer.

Savings, Economic Growth, and Demographic Change in the EU

It is evident from Mason’s (1988) study that there is a correlation between savings, economic growth, and demographic changes. It is common amongst the majority of industrialized countries that there is a primary concern toward population dynamics and economic development, which focuses more on the effect that a declining new population and an increasingly ageing population haves.

According to Mason (1988), a quickly growing population needs increased investment to conserve the labour to capital ratio and productivity.

Aside from the fundamental relationship between population growth, savings, and economic growth, the accretion of human capital and institutional and restructuring issues also play a vital role.

Based on the study (Mason, 1988), empirical evidence supports domestic savings as a significant investment source. Based on comparisons between countries in the EU-15, a correlation is revealed between the gross domestic savings ratio, the gross domestic investment ratio of 0.064, and the slope of corresponding regression being the value of 0.63.

This particular value is calculated from a one percent increase in savings from an increase in investment by 0.63 percentage points.

On the contrary, Solow’s (1956) neoclassical growth model asserts that savings do not influence the long-term growth of total and per capita output due to the capital being dependent on an increase of the capital and labour ratio and requiring an increase in the share of output to replace and maintain the capital that in already of existence.

Hence, Solow (1956) suggests that capital depreciation can ultimately lead to an excess of net investments. However, a continual increase in the labour force may augment the process as more workers will be equipped with capital.

Thus, under the neoclassical structure, an increase in investment provisionally enriches the growth rate and increases the level of output per worker.

Net investments, gross investments minus investment ardent for replacing depreciated assets, determine the definite intensification in a country’s actual value. On the contrary, there is no available data on net investment for many countries, which may be considered reliable.

This is correct mostly for time series data. As a result, many empirical studies use the gross investment to specify the resources accessible to increase a country’s physical plant.

For a lot of countries, net national savings can be decomposed into government savings and private savings. Furthermore, private savings can be further divided into corporate and household savings.

Leff (1969) investigated the impact of population growth on aggregate savings studied the life cycle of savings models linked to savings and demographic factors.

Leff (1969) also incorporated effects on the household level and the aggregate level too. Using the Leff (1969) structure, there is no similarity between current income and anticipated expenses as both consumption and earnings are assumed to vary in various ways over the life cycle.

With life cycle savings, households can shift income between various time stages to acclimatize to the method of preferred disbursements. During time periods when earnings are to exceed the desired expenditures, households end up saving, and the reverse occurs when earnings do not exceed the desired expenditures. Leff (1969) asserts that savings are highest in the middle of an individual’s life as they save for retirement.

The major source of investment, aggregate savings, depend on households’ savings currently working and currently retired households’ dissaving.

Based on the life cycle savings theory, a decline in fertility influences savings as there is a reduced burden on childbearing costs leading to less consumption and an increase in savings at a household level, known as the dependency effect; and also reduced fertility causes population ageing which results in relatively older households increasing (Wasmer, 2004).

Overall, older households typically, on average, have a lesser rate of savings, which results in reduced savings. In the scenario of a growing population, households containing the young and those who are saving outstrip those households with the old or those of the dissaving.

However, as a result, a growing population leads to an increase in aggregate savings, known as the growth effect. The dependency effect generally implies a negative relationship between rapid population growth and savings. The growth effect, on the other hand, means a positive relation to these factors.

The dependency effect and growth rate effect are based on the life cycle hypothesis related to microeconomic theory. However, on the macroeconomic level, changes in age structure affect savings as an increase of younger groups may increase consumption relative to production, which reverses with an increase in older groups.

The major risk of uncertainty that is related to the crisis can bring about a catastrophic effect. This will include Greek depositors having difficulty getting their money out of banks, resulting in scarce government services. It can impact voters running to the polls to elect new leaders amidst the crisis contributing to the financial mishap.

Greece’s role as a member state of the EU-19 is at stake, with the country having to exit the Euro. If the country is to leave the euro, a new drachma, Greece’s currency, would be worth less than a euro, with speculations saying that the drachma may be devalued by 50 percent leading to costs of imports skyrocketing and also further soaring inflation (CNN Money, 2015).

The economy of Greece has already shrunk by 25 percent, with unemployment rising to record levels, which will be discussed in the paper’s different sections. One in two young people are currently without work; wages and pensions have been cut, and many small and medium businesses have closed (CNN Money, 2015).

Aside from the terrible economic impacts of the crisis on Greece, various social implications have arisen. According to Hope (2012), it was reported that 20,000 Greeks were made homeless during 2012 and about 20 percent of shops in the historic centre of Athens have become abandoned.

Furthermore, an estimated 20 percent of Greeks no longer have enough money to cover daily food expenses (Zetichik, 2015). With the Greek government under significant pressure from its European creditors to cut expenditure, it could not provide a safety net for its citizens to rely on.

An example of this being a national program to move displaced people back to their homes through a stipend of a few hundred euros monthly which had severely faltered (Zetichik, 2015).

Further decisions of the Greek government can create a harsher living environment for Greek citizens who are already on the poverty line by willing to sign for another 4.4 billion euros worth of spending cuts to secure a deal with the bailout (Pop, 2012).

These budget cuts will amount to about 2 percent of the gross domestic product within the country’s defence, healthcare, and pharmaceutical spending (Pop, 2012).

IMF officials such as Poul Thomsen, overseers of the Greek austerity programme, asserted that Greeks were now at their limit of tolerance for austerity, citing that the Greek people had done enough in terms of reforms at a significant cost to the population (Pop, 2012).

This is evident from a New York Times report (2013), which showed the adverse conditions Greek families were living in. Due to an increase in tax requirements such as on heating oil; raising taxes to 450 percent, even though many middle and lower-middle-class citizens of Greece were facing wage cuts and outright unemployment, 80 percent of Greeks could not heat their homes for the winter season (NY Times, 2013).

This caused Greek citizens to turn to environmentally damaging solutions to heat their homes, including cutting down wood from forests giving rise to pollution in areas; such as Athens, where the city was already struggling with low air quality (NY Times, 2013).

According to Holodny and Udland (2015), local Greek businesses are in a state of disorder, with many Greeks now preferring merchandise and other tangible items over the euro. Greek banks have been closed since June 29 when the Prime Minister announced a referendum vote on bailout terms, a vote which came back as “NO.”

During this time, the Greek economy seized up, and banks began to run short of cash as assistance to the country from the IMF and ECB dried up after Greece failed to pay over 1.5 billion euros that were owed to the IMF on June 30, 2015 (Holodny and Udland, 2015).

Following the bank closures, capital controls set have limited ATM withdrawals at Greek banks to 60 euros per day Holodny and Udland (2015). The Figure below sums up the emotion and desperation that the Greek people are facing as the country as a whole prepares to deal with an insurmountable debt of 35 billion pounds. The image has been circulating all around social media and newspapers since the decision to limit ATM withdrawal.

Figure 4- Elderly Greek pensioner (Yam, 2015)

The image in Figure 4 is of 77- year old Greek citizen Giorgos Chatzifotiadis, one of many Greek pensioners who were adversely affected by the country’s debt crisis (Yam, 2015).

Chatzifotiadiswas photographed outside of an Athens bank, sobbing on the ground after not withdrawing a pension on behalf of his wife (Yam, 2015). Pension funds have lost about 2.5 billion euros since 2012 in Greece, which is backlogged with more than 400,000 pension applications to deal with, and this is considered to have added to the country’s existing tally of 2.65 million pensioners (Nardelli, 2015).

Alongside the package of savings and tax increases, Greece’s creditors demand the government cut pensions by an equivalent of 1 percent of the country’s GDP (Nardelli, 2015).

However, the Greek PM and his finance minister have not complied with the demands of the creditors. Several factors need to be taken into account for the pension system in Greece.

Firstly, solely based on the country’s demographic profile, Greece has about 20.5 percent of people over 65 in terms of its ageing population. Coupled with that is the youth unemployment rate, which is still above 50 percent.

Thus, the younger generations cannot generate funds to pay for elderly services such as pensions shortly. Furthermore, Greek society is very dependent on its pensioners.

According to Eurostat (2015), one in two households relies on pensions to make ends meet, while the country has an old-age dependency ratio that is well above 30 percent.

This means that for every 100 people of working age in Greece, at least 30 people aged 65 or more. Lastly, the allotted Greek pensions are not considered enough to live a sustainable life.

According to Nardelli (2015), an estimated 45 percent of pensioners receive pensions below the poverty line of just 665 euros per month.

There are numerous definitions and types of labour market shortages. However, commonly they refer to a situation where there is a need for the number of workers to exceed the available supply of them at a specific wage and working conditions at a specific place and point in time (OECD, 2003; Ruhs and Anderson, 2010, IOM, 2012). This paper distinguishes two main types of labour shortages;

– Quantitative shortages are caused by aggregate excess demand with insufficient workers to fill the overall demand.

– Qualitative shortages are caused by shortages in specific skills, occupations, or sectors with available workers not having the needed skills, preferences, or information to fill the shortages.

Keeping in mind the high unemployment rate in most regions of the EU resulting from the ‘Great Recession’ that began in 2009, quantitative labour market shortages are not considered a dire issue throughout most EU countries.

However, the European Commission (2015) hypothesizes that quantitative labour shortages have the potential to become an issue in the future if the labour force begins to diminish as a result of demographic changes while labour demand at the same time increases and the economy of each country begins to recover.

Demographic developments can explain the decline of the labour supply in the EU-15 member states and Greece by explicitly analyzing the decline in the working-age population and the decline in the working-age population’s participation rate.

According to Zimmermann et al. (2007), it is not easy to measure labour shortages. The fundamental labour market indicators for identifying labour shortages are rooted in economic theory and ambiguities that affect the practical application of those indicators. Labour shortages, or job vacancies, or excess demand are similar terms that mean open positions. Each of these is viewed as opposite to unemployment or excess in supply.

There is a chance for excess demand and excess supply to existing simultaneously. This may come from the fact that the labour skills that certain employers may want are not satisfied by the available collection, thus resulting in positions being left vacant.

According to OECD (2003), the discrepancy between labour demand (available jobs) and labour supply (skills of the unemployed) is defined as structural unemployment.

Firstly, it is necessary to examine the demand side of the labour market. Demand for labour is often recognized as a classic early indicator of the labour market’s vigour and well-being. When an economy is healthy, employers hire workers who, as a result, produce goods and services that the employers can sell the goods in the markets and earn a profit.

Hiring workers increases the costs for employers, who often want to hire workers at lower wages. Based on the law of demand for labour, an inverse relationship between the need for work and labour price is established and represented in a downward sloping curve.

Employers are only willing to hire extra workers when the marginal revenue product of labour exceeds nominal wages. Based on the use of cost benefits, this allows profits to be kept high.

When marginal revenue product of labour equals nominal wages, the business will have reached its maximum profits and then decide no longer to hire.

According to Eurostat (1997) projections, four discrete characteristics will exemplify between 1996 and 2020. They are as follows;

Based on these characteristics, it is evident that the ratio of the elderly to the young will increase drastically, resulting in dramatic changes within the population.

Based on these assumptions, the median age will increase from 36 to 45 years, and the proportions of those aged under 20 years and over 65 years will be reversed by the year 2020.

The three major groups of children/students, active population, and retired adults, witness a dramatic change in their numbers and proportions, giving it a more significant chance for a shortage in labour within Greece.

A decrease in the working-age individuals’ population can be caused by a common output of the working-age population that is greater than the input caused by ageing and low fertility rates, as evident in sections 2.2 and 2.3. Another factor that impacts this trend is net emigration.

Figure 5- Beveridge Curve 2006-2014 (Source; Eurostat)

Due to the low and decreasing fertility rate in the last fifteen years, young people’s inflow into the labor force is smaller than the outflow of older workers who retire.

If activity rates remain the same, this will decrease the labour force, causing a constricted labour market in which labour demand surpasses labour supply. According to OECD (2003), towards the middle term of the projection, the ever-increasing number of “baby-boomers” that are scheduled to retire will, in some occupations, lead to a replacement demand that will be more difficult to fill from the domestic labour supplies in the EU.

Table 2- Highest correlations and corresponding lags of TFR with various indicators of economic recession by country, 2000-2011 (Source; Eurostat, 2014)

Table 2 above illustrates the correlations between the time series of the total fertility rates changes and a selection of indicators of an economic crisis in each selected European country.

This test’s main point was to look for potential connections between economic conditions and changes in fertility behaviour. The correlations were calculated by considering a lag in the total fertility rates from 0 to 3 years.

Thus, four correlations were calculated for each country and indicator. The Table above thus represents the highest values of the correlations, either negative or positive, coupled with the lag at which each of those computations was found.

To emphasise and remain focused on the economic crisis’s effect, data from 2000 to 2011 was used to calculate the annual data obtained from Eurostat databases.

Based on the correlations, it was found that the usual indicator of economic growth based on the GDP of each country shows an expected relationship of negative changes in GDP corresponding to negative changes in TFR, with a delay, resulting in a high positive correlation at specific lags as highlighted in the Table.

Aside from GDP, another indicator chosen was actual individual consumption (AIC). It provides a more resolute measure for households’ material welfare conditions since it refers to individuals’ goods and services regardless of the individual’s governments purchased those goods, or non-profit organizations.

By correlating the changes in AIC to TFR, the study analyzed the impact of changing household material situations on fertility behaviour; rather than the living standards of a country, which is measured instead using GDP. Next, the age group’s annual unemployment rate of age group 15-49 was used as an indicator represented with (UNE).

The anticipated relationships are those with a negative sign as they mean that a positive change of the UNE is correlated with a negative change of the lagged total fertility rate. Lastly, the indicator used in Table 6 was the annual average consumer’s confidence index represented by (CCI).

This meant for the indicator to compute the mawkishness of economic uncertainty, the correlation between changes in CCI and lagged changes in TFR was expected to be positive.

By 2000, more than 20 million people were unemployed in 28 European Union countries, which corresponds to approximately 9.2 percent of the total labour force. Unemployment in Greece also follows the same trends as those of the EU-28. Nonetheless, between 2000 and the start of 2004,

Greece’s unemployment rate was above that recorded in the EU-28. After the economic crisis in 2009, unemployment increased at a rapid pace except for the years 2010 and 2011, where it only declined temporarily.

The unemployment level peaked at 19.2 million in the first half of 2013 before it began to decrease in the second half of 2013 and the beginning of 2014 until the end of the year. The trends described have been illustrated in the Figure below:

Figure 6- Unemployed persons, in millions, EU-28 and Greece, 2000-2015 (Source; Eurostat)

Youth (ages 15-35) unemployment rates are seen as being higher, considerably more than double than compared to unemployment rates of all ages, as illustrated in Figure 18 below.

The economic crisis severely impacted the youth, with the second quarter of 2008 seeing the youth unemployment rate taking an upward trend to peak at 23.8 percent in the first quarter of 2013 before beginning to decrease to 21.4 percent towards the end of 2014.

Figure 7- Youth unemployment rates, EU-28 and Greece. 2000-2015 (Source; Eurostat)

Employment rates are seen to be generally lower for both women and older workers. Based on our findings for 2014, men’s employment rate was at 70.1 percent in the EU-28 compared to 59.6 percent for women, which is evident from Figure 9. Also, male employment rates were seen to be unswervingly larger than those for women throughout all EU-15 member states in 2014.

Based on Figure 9 Italy and Greece recounted gender differences of 16 to 18 percentage points for statistics detaining employment rates. Both countries reported the lowest and highest female employment rates. However, in countries such as Finland and Sweden, there is very little difference between both genders’ employment rates.

Just as with female employment, there is also evidence that suggests the employment rates for older wor in 55-64 aged group has increased at a rapid pace, even though the countries were facing a financial and economic crisis.

In Figure 9, in 2014, 11 EU-28 member states had higher employment rates for older workers between 50 percent and 66 percent. However, for the EU-15 countries, the highest employment rate for older workers was found in Sweden, which has 74.0 percent employment.

The Greek Debt Crisis has caused a great deal of upheaval throughout Greece and the European Union. Several other countries faced the same deteriorating economic conditions as the Greece government. The country has seen an increase in its unemployment rate and labour shortages due to many factors that are far from the crisis’s immediate economic impacts.

The Greek government played a direct role in producing the crisis, which is evident from its deceptiveness in understating its economic figures. This led to Greece being fragile and eventually being shut out of receiving further international funding and investment.

The Greek debt crisis can improve if the government agrees to the aid packages that have been suggested by the “Troika,” which is a group composed of the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, and the European Central Bank.

However, the European Union will need to revise various treaties and requirements once again that it has made in the Union. The German-dominated European Central Bank has provided the remainder of the European Union with a monetary policy that is adequate and workable for Germany.

Still, it places countries such as Greece in a tight spot and a depression. Greece has been squeezed into a crushing debt burden of 177 percent of GDP and deep depression, making it difficult for the country to raise funds needed to make timely debt payments. Therefore, the EU’s economic policies need to change to accommodate poorer countries to grow and prosper.

Allison, G. T., and Nicolaidis, K.. (1997). The Greek Paradox- Promise vs Performance. Cambridge, MA: J.F.K. School of Government.

Ark, B. V., O’Mahoney, M., and Timmer, M. P., (2008). ‘The productivity gap between Europe and the United States: Trends and causes.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22 (1), pp132-144.

Bairoch, P. (1976). Europe’s GNP 1800-1975. Journal of European Economic History, 5, pp. 273-340.

Beine, M., Docquier, F., and Rapoport, H.,. (2006). ‘Measuring skilled international migration: New estimates controlling for age of entry.’ World Bank Research Report.

Beine, M., Docquier, F., and Rapoport, H.,. (2008). ‘Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: Winners and losers.’ The Economic Journal, 118, pp 631-652.

Blanchard, O., and Wolfers, J., .(2000). ‘The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of European unemployment: The aggregate evidence. Economic Journal, 110 (462), pp 239-253.

Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., and Rau, R., 2009. ‘Ageing populations: the challenges ahead.’ Lancet, 374, 1196-1208.

CNN Money. (2015). The huge risks of the Greek debt crisis. CNN Money. Available at: http://money.cnn.com/2015/06/29/news/economy/greece-

crisis-five-big-risks/ (Accessed: 29 June 2015).

Fotakis, C. and Peschner, J., .(2015). ‘Demographic change, human resources constraints, and economic growth.’ The European Commission, working paper 1/2015.

Gruenberg, E.,. (1977). ‘The failures of success.’ Mill Mem Fund, 55, 3-24.

European Commission (EU). ( 2015a). ‘The 2015 ageing report- Economic and budgetary

projections for 28 EU member states (2013-2060).’ European Union. Belgium:

Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

European Commission (EU). (2015b). ‘The 2015 ageing report- Underlying assumptions and

projections methodologies.’ European Union. Belgium: Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.European Commission (EU). (2015c). ‘Unity, solidarity, diversity for Europe, its people and its

territory.’ Europa. Retrieved from :

http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/contentpdf_en.htm.

Hope, K. (2012). Grim effects of austerity show on Greek streets. Financial Times. Available at: from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/95df9026-5983-11e1-8d36-

00144feabdc0.html (Accessed: 2015).

Holodny, E., and Udland, M. (2015 Jul. 9). A Greek jeweller turned down a million-dollar offer,

and a travel-agency boss said ‘We are all going to die’. Business Insider- Finance.

Available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/greek-life-during-

euro-crisis-2015-7 (Accessed: 9 July 2015).

Kostis, K., and Petmezas, S., (2006). Development of the Greek Economy in the 19th Century.

Athens: Alexandria Publications.

Lisbon Council. (2011). Euro Plus Monitor Report- Progress Amid Turmoil. [Report], Berenberg

Bank.

Macunovich, D. J.,. (2002). ‘Birth Quake: The Baby Boom And Its Aftershocks.’ Chicago, IL,

USA: University of Chicago Press.

Maddaloni, A., Musso, A., Rother, P., Ward-Warmedinger, M., and Westermann, T.. (2006). Macroeconomic implications of demographic developments in the Euro area. European Central Bank, Occasional paper series, No. 51., European Central Bank Publishing.

McMorrow, K., and Roeger, W.,. (2011). ‘The economic consequences of the ageing population.’

Europa Finance, 5, (1), pp 3-72.

Nardelli, A. (2015 June 15). Unsustainable futures? The Greek pensions dilemma explained. The

Guardian- Finance. Available at:

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/15/unsustainable-futures-greece-

pensions-dilemma-explained-financial-crisis-default-eurozone (Accessed: 15 June 2015).

Pop, V. (2012) IMF worried by the social cost of Greek austerity. EU Observer. Retrieved from

Available at: https://euobserver.com/economic/115104 (Accessed: 2015).

Preston, S. H., Himes, C., Eggers, M., 1989. ‘Demographic conditions responsible for population ageing.’ Demography, 26, pp 691-704.

Saint-Paul, G., (2004). ‘The brain drain: Some evidence from European expatriates in the United States.’ CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 4680, Centre for Economic Policy Research Publication.

Salt, J.,. (1997). ‘International movements of the highly skilled.’ OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 3, OECD Publishing.

Skartsis, L. S., (2012). Greek Vehicle & Machine Manufacturers 1800 to Present: A Pictorial History. Marathon Publications.

The New York Times. (2013). Greece’s Debt Crisis Explained. The New York Times. Available at:

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/business/international/greece-debt-

crisis-euro.html?_r=0 (Accessed: 2015).

Tremmel, J. C. (Eds.)., (2010). A Young Generation Under Pressure? London, UK: Spinger-Verlag

Wasmer, E., (2004). ‘Interpreting Europe-US labour market differences: The specificity of human capital investments.’ American Economic Review, 96(3), pp 811-831.

Yam, K. (2015). After seeing a photo of a Greek man crying outside the bank, the CEO in Australia

vows to help him. Huffington Post. Available at:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/07/08/greek-debt-crisis-pensioner-

crying_n_7746640.html (Accessed: 8 July 2015).

Yoon, J. W., Kim, J., and Lee, J.,. (2014). ‘Impact of demographic changes on inflation and the macroeconomy.’ IMF Working Paper, 14/210, International Monetary Fund Publishing.

Zeitchik, S. (2015). For many in Greece, the economic crisis takes a major toll: their

homes. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved fromAvailable at:

http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-greece-crisis-homelessness-

20150620-story.html#page=1 (Accessed: 20 June 2015).

Zhang, J., Zhang, J., and Lee, R.,. (2003). ‘Rising longevity, education, savings, and growth.’ Journal of Development Economics, 70, pp 83-101.

Zimmermann, K. F., Bonin, H., Fahr, R., and Hinte, H., (2007). ‘Immigration Policy and the Labor Market: The German Experience and Lessons for Europe. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag

The time required to write a master’s level full dissertation varies, but it typically takes 6-12 months, depending on research complexity and individual pace.