Here is a sample that showcases why we are one of the world’s leading academic writing firms. This assignment was created by one of our expert academic writers and demonstrated the highest academic quality. Place your order today to achieve academic greatness.

The current project examines sustainable design in light of its principles and the economic value that it may bring to owners Ash Developments of Unit 19 building a 4 storey office premises. The report devised uses the case study of Unit 19 to analyse if sustainable design principles apply to the building’s repair and renovation.

Various sustainable design principles were examined, with overlapping features found in each literature reporting principle. The overlapping principles were then used to devise a specific set of sustainable design principles that needed to be followed through the design process and implementation of unit 19 repairs and renovations.

Unit 19 was facing various repairs, which included some of the following;

1. Localised repairs on the asphalt roof coverings.

2. Redecoration of fourth-floor extension and plant room structure on the roof level.

3. Exposure of steel reinforcement bars with corrosion signs on the windows’ concrete cills, lintels, and piers.

These repairs and an extensive list of repairs mentioned in the current report were fixed using sustainable design. For the current study, sustainable design is defined as ecological designs that ensure that humans’ actions and decisions made in the present do not constrain future generations’ opportunities to come.

Using this foundation, the entire design for the renovation was developed to ensure the practical use of ecological methods to build a financially viable investment for the owners, a comfortable work environment for the occupants, and building a key aspect in the eco-system of Liverpool.

Ash Developments is looking for consultation on incorporating sustainable design into one of the office properties, unit 19, Liverpool Innovative Park, Edge Lane, Liverpool. The property itself comprises four storeys that have been extended into a partial fifth floor over the roof area. The property is primarily for office premises and built into an “L” shape with a curved bullnose detail to the northeast.

The property has been fitted as office space with both open plan and cellular office arrangements. Based on the property’s inspection found in the case study, it is generally reasonable based on its age and use. However, there is a need for various repairs to the building in which the landlords would like to know if the sustainable design is feasible to them.

The current report aims to examine sustainable design choices in light of the significant fixtures required from the inspection of unit 19. The analysis of sustainable design will be undergone using sustainable design principles, which will be researched. The chosen sustainable design principles will be used as guidance to propose a strategic plan that can encompass all the repairs recommended from the inspection.

The current report aims to propose a programme that tackles external repairs;

• Spalling concrete to the elevations which poses a surmountable health and safety risk

• Repairs on roof coverings

• Repairs on parapet walls and windows

• All repairs need to be environmentally friendly by using sustainable design regarding the process, material, and implementation.

The research also aims to investigate various sustainable designs best suited for the requirements set out by Ash Developments. This will include using green technology or construction if it is proven that sustainable design will positively impact the unit 19 building. Other aims of the research include;

• Investigating the research questions; what is sustainable design and green construction? How can sustainable designs be implemented into the case study’s unit 19 building?

• Examine the financial aspects, which include the advantages and disadvantages of using sustainable design.

• Examine and scrutinise the various proposed strategies and recommendations for repairing unit 19.

The current report proposes to reach its aims through the following objectives;

• Analysing solutions to the immediate repair problems faced in terms of eco-friendly designs and non-eco-friendly options.

• Analyse the client’s financial concerns about sustainable designs on the existing unit 19 building.

• Analyse the current trends and technologies available for sustainable design within the construction and architecture industry that can be implemented to unit 19, the building under question for repairs.

Orders completed by our expert writers are

According to DeKay and Brown (2014), sustainable architecture and construction aim to mitigate the negative environmental impact that buildings may have through efficiency and moderation regarding the type and amount of material used in construction and the energy and development space needed to construct it.

Furthermore, the heart of sustainable architecture keeps in mind that there is a need to use sentient methods for energy and ecological conservation to design the built environment (DeKay and Brown 2014).

The whole purpose of the sustainability philosophy of ecological design is to ensure that humans’ actions and decisions made in the present do not constrain future generations’ opportunities to come.

There are various architectural design principles and processes used to become the foundation of sustainable building design. For example, Van der Ryn and Cowan (1996) set out five principles that embodied the view that transformation into a more sustainable world needs to use a more renewed approach to building buildings and products by incorporating the basic understanding of ecological principles.

Vale and Vale (1991) described six principles as the foundation for the green design process they practically implemented through the Hockerton Housing project.

At the same time, Roaf (2004) focuses mainly on the continuous climate change issue and emphasises designing resilient buildings that can minimise further environmental damage, focusing on a building’s longevity and low use of energy.

Regardless of the various principles of sustainable design that are found extensively through literature, certain principles overlap. As a building surveyor, it is essential to analyse the various sustainable design principles common among the practical application. Therefore, from extensive literature research, the following principles were highlighted and used throughout the current report.

At first glance, it may seem that sustainable design is out of many contractors’ and property owners’ realm. However, the various related building systems that form a relationship are elemental to the building’s overall functionality.

For example, maximum energy efficiency can be achieved within a building through various building systems such as the controllability of lighting systems on an individual and overall building system level, reduction of light pollution, and light fixtures’ efficiency to optimise the entire building’s energy performance.

There is mounting evidence that sustainable buildings can provide their owners, operators, and occupants with many benefits or rewards. First and foremost sustainable buildings have lower annual costs for energy, water, maintenance/repair, the need for reconfiguring space from changing needs, and other operating expenses associated with commercial buildings. The reduced long-term costs don’t need to come at a higher expense than first-time costs.

According to Jennings (1995) and Dekay and Brown (2014), through the use of integrated designs and innovative services of sustainable materials and equipment, the first time costs of a sustainable building can be considered the same or even at times lower than traditional building methods of design and construction.

Aside from the direct cost savings, buildings built or renovated from sustainable design can provide indirect economic benefits to the building owner and society. For example, Kim (1998), DeKay and Brown (2014), Bejan (2015) all state that sustainable buildings can promote better health, increased comfort and well-being, and productivity of the building occupants.

This, in turn, can reduce absenteeism within a working environment and increase the productivity of the active individuals in the workplace environment. There are also substantial economic benefits to the buildings’ owners, including lower risks, longer building lifetimes, improved ability to attract new customers, reduced expenses of dealing with complaints, less time, and lower costs for project permitting value. For the society at large, sustainable buildings offer economic value and reduced costs from air pollution damage and lower infrastructure costs.

Many of the principles outlined above can be incorporated into the sustainable design for unit 19, which will be discussed in length in the strategic plan section.

Sustainable design will begin with the conceptual stage to build on ideas to realise the full benefits of the design. The first step that needs to be taken is by building up a design team. This design team will include the owners (Ash Development), architects, engineers, sustainable design consultants, landscape designers, health, safety, security experts, general contractors, cost consultants, and considerable key subcontractors.

The composed team will conduct a series of 15-day workshops and meetings to discuss the project goals for unit 19, keeping in mind the owner’s wishes and the repairs required as extracted from the inspection report.

4. Localised repairs on the asphalt roof coverings.

5. Redecoration of fourth-floor extension and plant room structure on the roof level.

6. Exposure of steel reinforcement bars with corrosion signs on the concrete cills, lintels, and piers of the windows.

7. Vertical cracking of low-level brickwork most likely caused by thermal movement.

8. Repair glazed units on extension and another window repair.

9. No provision for smoke/heat detection to the office areas.

10. No accessible parking space within proximity to the main entrance.

11. There is a strong need for external repairs, particularly spalling concrete to the elevations, with remedial work needed on the roof covering, parapet wall, and windows.

These eight points of repairs need to be taken as a key in the repair and renovation of unit 19. All of the repairs mentioned above can be achieved through sustainable design. Along with immediate repairs, it is also necessary to reduce the overall energy use to make it a more ecological building. There is also a need to improve the overall ecology of the building site.

| Principles | Process |

|---|---|

| Ecological Design- designs made with nature in mind. The need for ecological accounting to take place in unit 19. | Environmental Brief- overview of carbon reduction, energy-efficient, creation of a flexible working environment. |

| Green Architecture- working with climate change conditions. The need to ensure that there is a conservation of energy or reduce energy consumption. Respecting the building site and encouraging that respect to future occupants. Minimising the use of new resources to repair the site. | Parameters- Enable the newly renovated site to be at least a “B” listed building. Ensure that the budget laid out is not overly strained. However, no construction project is void of cost creep. |

| Adapting Building for climate change- Through a good design, there needs to be little energy use as possible. There needs to be a reduction in the waste within the operations of construction and demolition. Ensure that future occupants and current workers of the project are comfortable and can survive the weather’s extremities. | Environmental Strategies- passive design is to be used for unit 19 to achieve natural ventilation and improve thermal performance. There needs to more landscape work on the site to promote biodiversity. |

| Evaluation methods- BREEAM measure ‘excellent’ on the renovated site. There needs to be constant monitoring of water, energy, and CO2. |

Reducing energy consumption is the top priority of the design goals for unit 19 and the repairs required by inspection. It is essential to establish natural light in the building without overheating the interior or making natural light uncomfortable, which often happens from glare.

The strategies developed for energy consumption reduction were evaluated based on their life cycle costs, including evaluating the equipment functionality, maintenance, repair, and replacement costs throughout its lifetime. Various modifications to components will be analysed for their implications in overall operational energy consumption, which will allow for a combination to be formed of all the modifications.

The strategy used for choosing and implementing insulation in the building must consider the comfort of occupants, which will analyse how energy is transmitted based on its direction and intensity. Since there are chances of energy usage from day to night and season to season, the use of materials becomes a high-ranking priority in reducing energy consumption.

By installing an innovative technology unit, 19 buildings will be electrical buildings, with the occupants using utility bills to track their energy usage. A similar project was undertaken for the Alliance Centre through the Alliance of Sustainable Colorado, a non-profit organisation to advance sustainability. The organisation had purchased a 100-year old warehouse for significant renovations.

However, since its sustainable renovation, the building has seen an increase by double in its occupancy. Simultaneously, it reduces the energy that it is using through conservation measures (NBI, n.d.). Based on the same renovations being made on the unit 19 building, it is hypothesised that unit 19 will be able to reduce the consumption of energy by 22 percent, making the use of energy 55 percent less than the average offices in the UK of 42 kBtu/sf/yr (Pearce et al. 2012). The average of all offices in the UK is a reasonable basis for comparing buildings of the same class.

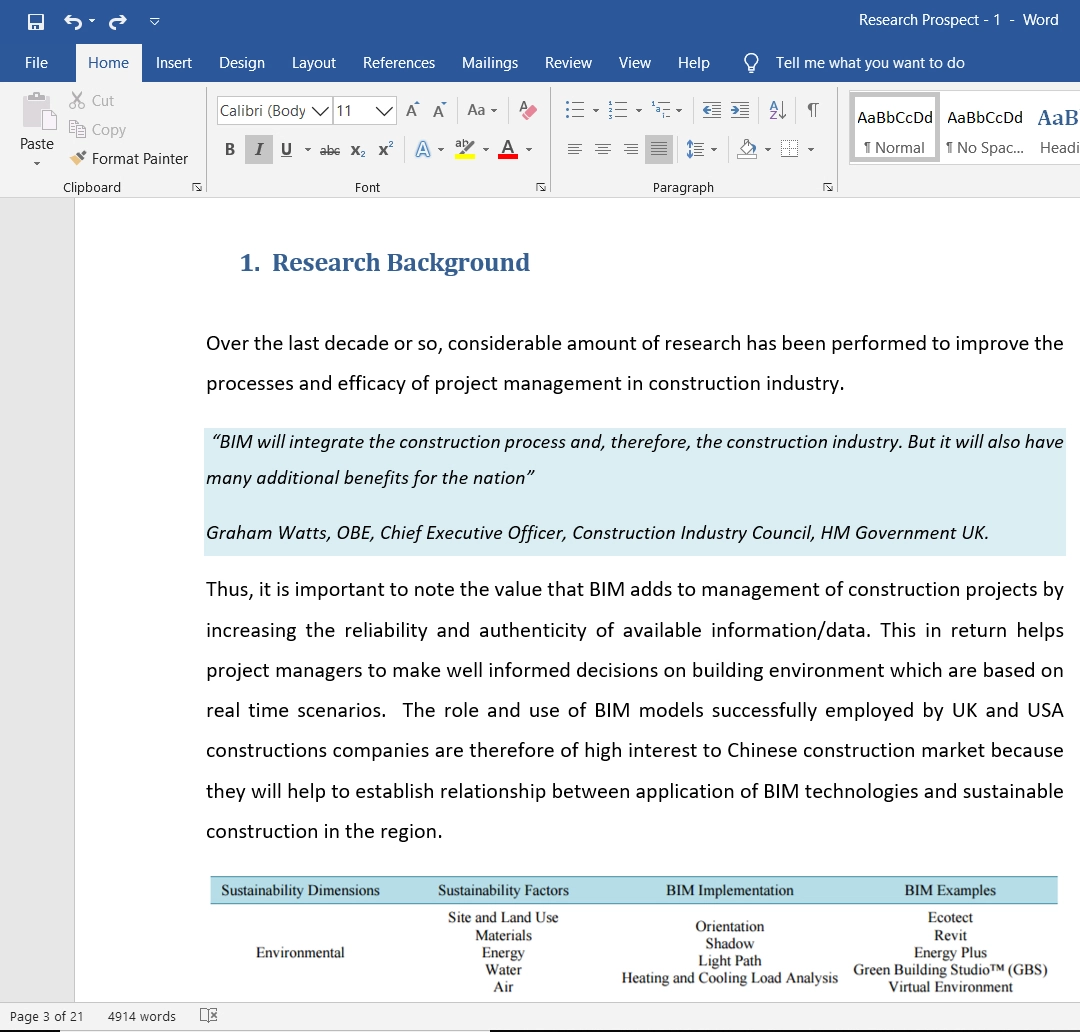

Figure 1- Energy Use per sq. ft. Comparison

A hypothetical projection of Unit 19’s energy consumption was built based on the renovations concluded in the building for energy efficiency. Afterwards, the office space’s full occupation was estimated along with its energy consumption for 45,765 sq. ft. office space using the Alliance Centre model (NBI, n.d.).

Based on the assumptions made, the building’s energy consumption is compared, as illustrated in figure 1. Based on the figure, Unit 19 will consume 39 percent less energy than average comparable office buildings.

Furthermore, on a national scale, the unit 19 building will use 55 percent less energy than the average of all UK office buildings (Bejan 2015).

The project’s entire construct for installing energy performance equipment will equal £82,276 at £2.16/SF after settlement incentives (NBI, n.d.). Funding for the renovations can be sourced from local ecological and sustainable energy companies and public works that fund energy management and conservation. The total time of renovations for energy efficiency will take a total of 5 months.

A design was proposed to integrate ecological concepts to make the unit 19 building environmentally friendly and economically viable from reviewing the sustainable design principles used. The remainder of the repairs immediately needed has been highlighted in the table below to indicate the repair recommendation.

| Recommendations | Repairs |

|---|---|

| Localised repairs on the asphalt roof coverings. | Repair roof using recycled content shingles. Are a low-cost alternative with a 50-year product life. |

| Redecoration of fourth-floor extension and plant room structure on the roof level. | Implementation of green installations and expansion of plant room on roof level to mimic garden roof. Adds insulation in cooling building, cleaning the air, and reducing the stormwater that gathers on the roof. There may be a need to have structural reinforcement to support the weight of the plants and soil. |

| Exposure of steel reinforcement bars with corrosion signs on the concrete cills, lintels, and piers of the windows. | Re-cement the concrete with sustainable mixed concrete, which mixes resources such as glass into the concrete without changing the mixture’s composition (Lemay et al., 2013). |

| Vertical cracking of low-level brickwork most likely caused by thermal movement. | Installation of bio-bricks to cover up the cracking of low-level brickwork (bioMason 2015). |

| Repair glazed units on extension and another window repair. | Replacement of all windows of the building with thermally insulated, solar control, and noise reduction glazing. Will allow |

| No provision for smoke/heat detection in the office areas. | Installation of smoke/heat detection alarms and sprinklers into the office areas and lobby. |

| No accessible parking space within proximity to the main entrance. | Addition of accessible parking space within proximity to the main entrance. |

In addition to the recommendations made on the repairs of the building. It is also recommended that the parking area include more ecological options, such as more green grass, trees, and flora, to beautify the region and make it more ecologically diverse. Landscaping experts will devise a parking lot plan that maintains the parking space’s functionality while also decorating the area using plants and flowers that will maintain themselves in the Liverpool environment in terms of temperature and seasonal changes.

Bejan, A (2015) Sustainability: the water and energy problem, and the natural design solution. European Review, 23 (4), p. 481-488.

BioMason (2015) the bioBrick. [online] Available from < http://assets.c2ccertified.org/pdf/Biobrick.pdf> [Accessed 4 March 2016].

DeKay, M and Brown, G Z (2014) Sun, Wind, & Light- Architectural Design Strategies. John Wiley and Sons: NJ.

Emmanuel, R, and Baker, K (2012) Carbon Management in the Built Environment. Routledge

Enright, S (2002) Post-occupancy evaluation of public libraries. Library Quarterly, 12, p. 26-45.

Finnegan, S, and Ashall, M (2014) The true carbon cost of new sustainable technologies. RICS Construction Journal, June/July 2014 p. 18 to 19.

Gasbay, H, Meir, I A, Schwartz, M and Werzberger E (2014) Cost-benefit analysis of green buildings: An Israeli office buildings case study. Energy and Buildings, 76, p. 558-564.

Grierson, D, and Moultrie, C (2011) Architectural design principles and processes for sustainability: Towards a typology of sustainable building design. Design Principles & Practices, An International Journal, 5(4), p. 623-634.

Hartigay, S.E & Yu S.M (1993) Property Investment Decisions, Spons.

Hover, K C., Bickley, J, and Hooton, R D (2008) Guide to Specifying Concrete Performance Phase II Report of Preparation of a Performance-based Specification for Cast-In-Place-Concrete. RMC Research and Education Foundation, Silver Spring, MD.

Jennings, J.R. (1995) Accounting and Finance for Building & Surveying. Macmillan

Kim, J J, (1998) Introduction to sustainable design. National Pollution Prevention Center for Higher Education. The University of Michigan, p. 1 to 28.

Lemay, L, Lobo, C, and Obla, K. (2013) Sustainable concrete: The role of performance-based specifications. National Ready Mixed Concrete Association. [online] Available from http://www.nrmca.org/sustainability/Specifying%20Sustainable%20Concrete%204-24-13%20Final.pdf. [Accessed: 3rd March 2016].

McLennan, J F (2004) The Philosophy of Sustainable Design. John Wiley and Sons: NJ.

New Building Institute (NBI) (n.d.) Alliance centre case study. [online] Available from https://www.bayren.org/sites/default/files/Alliance_Center_Denver_CO-Case_Study.pdf. [Accessed: 4 March 2016].

Oseland, N A (2007) British Council for Offices Guide to Post-Occupancy Evaluation. London: BCO

Pearce, A, Han Ahn, Y and HanmiGlobal (2012) Sustainable Buildings and Infrastructure – Paths to the future – Earthscan

Preiser, W F E, Rabinowitz, H Z, and White, E T (1988) Post Occupancy Evaluation. Nostrand Reinhold: New York.

Roaf, S (2004) Adapting buildings and cities for climate change: A 21st-century survival guide. Architectural Press: Oxford.

RICS Professional Guidance Sustainability: improving performance in existing buildings. 1st Edition, Guidance Note GN 105/2013.

RICS Guidance Note- Environmental Impact Assessment.

Robert, C (2003) White paper on sustainability. Building and Construction, White Paper R2, p. 1-48. [online] Available from: https://www.usgbc.org/Docs/Resources/BDCWhitePaperR2.pdf.. [Accessed: 4th March 2016].

Ryan, C (2006) Dematerialising consumption through service substitution is a design challenge. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 4(1), p. 3-6.

Shu-Yang, F, Freedman, B, and Cote, R (2004) Principles and practice of ecological design. Environmental Reviews, 12 (4), p. 97-112.

Vale, R and Vale, B (1991) Green Architecture: Design for a Sustainable Future. Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London.

Van Der Ryn, S and Cowan, S (1996) Ecological Design. Island Press: Washington, DC.