Here is a sample that showcases why we are one of the world’s leading academic writing firms. This assignment was created by one of our expert academic writers and demonstrated the highest academic quality. Place your order today to achieve academic greatness.

The current study examined what factors influence a customer’s behavior to switch from shopping online to traditional brick-and-mortar stores. The study looked to examine this phenomenon using the

Theory of Planned Behaviour. A model was constructed using this theory to analyze hedonic beliefs, utilitarian beliefs, hedonic products, utilitarian products, self-efficacy, time, information, money, normative beliefs, and perceived behavioural control.

The study has used a quantitative research approach to study the factors influencing customers to switch from the internet to stores. The research’s approach leads to the use of a Likert-like scale survey as the quantitative research instrument.

The data obtained was then put through frequency analysis and regression analysis in addition to a Cronbach’s alpha analysis to test the instrument’s reliability.

The tests produced a result that indicated that the most influential factors that contributed to channel switching were Utilitarian beliefs, Utilitarian products, self-efficacy, information, and attitude based on the regression analysis result.

The research instrument constructed was also reliable because the alpha product produced was in the excellent category. Retailers can use these results to develop Omni-channels that take into account these factors contributing to channel switching.

Retailers ranging from department stores to speciality stores have launched internet sales sites parallel to pre-existing retail channels (Hoisington et al., 2015).

Many traditional retailers have used the Internet to channel consumers as a logical extension of their store’s physical existence to complement existing customer relationships, business processes, and merchandise distribution (Prince & Graf 2015).

According to Scott Silverman, “branding is a tremendous advantage, and cross-promoting it over the internet, and physical stores will open up new selling opportunities” (Bernstein et al. 2008).

Conversely, based on the latest reporting from news agencies, many companies that had started as internet sensations are adopting the model of traditional brick and mortar stores < vital>(Schneir et al., 2014).

According to Walsh (2016), Amazon.com had opened its first brick-and-mortar store in November in Seattle’s University Village, USA.

Over the last few years, many US and UK companies have launched a physical presence to market their products better, build closer customer relations, and boost their online traffic and sales (Glanz et al., 2012).

Shifting from online presence only to conventional stores is reflecting the broader industry placing a greater deal of importance on omnichannel retailing, which allows merchants to set a goal of providing customers with a seamless experience regardless of if they are shopping through a computer or mobile device or a traditional retail store (Baal and Dach 2005)

Shim et al. (2000) argue that the consumer market of today is driven by various factors such as dual-income families, decreasing amount of available shopping time, revolutionizing technology, and innumerable shopping choices among different products, brands, and diverse retail formats like brick-and-mortar or online shopping using electronic mediums.

Pookulangara et al. (2011) have asserted that retailers are beginning to learn that many shoppers are taking advantage of the variety of available channels allowing them to shop more often across different sales channels.

Sullivan and Thomas (2004) describe this behaviour as consumer channel migration, a process by which current consumers repeatedly choose to frequent one of several retailer channel options such as; brick-and-mortar catalogues/mail orders.

Wise et al. (2004) found that multiple complementary channels provide more diverse service outputs than compared to use of single-channel strategies allowing retailers to increase their consumer contact points; when it adds on a channel, it can expand both the quantity and possible combinations of service outputs available to its consumers.

Pookulangara et al. (2011) find that the retail industry has matured, and expansion has slowed to a steady crawl causing retailers to find new ways to create shareholder value using the least amount of assets disposal.

Pookulangra et al. (2011) further recognize that multi-channel marketing is different from the traditional route of multiple-channel marketing.

Firms interact with different segments of their consumers through different channels. Pookulangra et al. (2011) believe that multi-channel marketing is more about consumers using alternative channels to build a network relationship with the retailers when they please. These consumers can also use different channels at different times.

This is why many brick-and-mortar retailers now have websites, while many internet-based retailers are moving towards building physical stores (Rangaswamy and Burggen 2005; Kurt Salmon Associates 2005).

Sullivan and Thomas (2004) found that the consumer channel migration characteristic is imperative in consumer relationship management since consumers who can buy from various channel combinations may differ regarding the significant drivers of consumer profitability.

Johnson (1999) argued that multi-channels could meet the desires for consumers’ flexibility when it comes to shopping “what they want when they want, and in a way that they want.”

However, the problem that arises, which is relevant to the current study, is understanding how and when consumers use retailers with physical locations or the Internet and what drives their propensity to switch from the Internet to brick-and-mortar internet-based companies to switch to such an option.

Based on the research question presented in the section below, the study’s primary aim is to analyze how consumers have influenced businesses to shift back to traditional retailing, brick and mortar stores using the Theory of Planned Behaviour.

The theory assumes that individual attitudes and beliefs, in addition to many subjective norms and control factors, will result in an intention to perform a specific behaviour, i.e., to switch from online shopping to traditional shopping. To achieve this aim, the following objectives need to be met.

The current study is based on a primary research question that will form its basis.

How has consumer behavior influenced the shift of click-and-order stores to more traditional retailing with physical stores?

Complimentary questions to the primary research question were also developed to aid the research of the current. Complementary questions included;

The current study uses the theory of planned behaviour (TBP) to analyze consumers’ channel switching behaviour by switching from the Internet to brick-and-mortar stores. Ajzen (2001) explains that planned behaviour theory predicts and explains human behaviour in specific contexts.

For this specific study, the context used is switching channels while shopping, precisely the combination of brick-and-mortar stores and the Internet as a medium of retailing. This theory’s main factor is an individual’s intention to perform a given behaviour under volitional control. The theory hypotheses that behavioural intention is the direct originator of the actual conduct.

The theory of planned behavior assumes that an individual’s attitudes and beliefs, when coupled with subjective norms and control factors, result in an intention to perform a specibehaviorioase switching from the internet to traditional retail stores.

The current chapter aims to analyze the current and previous literature for examining consumer behaviour in channel switching and existing business models that companies are using to attract consumers towards their multiple-channel network.

The literature used in the current study does not set a geographic limitation but attempts to encompass a great deal of literature that has been conducted outside of the UK. Previous studies investigating these phenomena have examined shopping benefits and costs of multi-channel consumerism using individual channels like traditional stores, catalogues, television, and the Internet (Balasubramanian et al., 2005).

However, with the rise of the Internet, e-commerce, and the increased number of online retailers, studies have begun to examine consumers’ attitudes towards using different purchasing channels and channel switching behaviour. Using the concepts and theories discussed in the current chapter, the study will implement its literature review findings in developing a research approach and methodology.

Today, consumers are taking a more active role in their shopping and making decisions about products. Because of this more aggressive role, they demand any time and where procurement in addition to any time and where consumption of products or services.

Consumers are beginning to demand more value in exchange for their money, time, effort, and space in the four primary consumer resources (Seth and Sisodia 1997).

Due to this increased active role that consumers have taken on, they drive the entire marketing process for companies (Baal and Dach 2005) while also demanding increased business customization.

Crawford (2005) asserts that a singular marketing plan is no longer effective for the whole target segment since individuals are now beginning to expect companies to respect their individuality, demanding personalized marketing strategies that comply with their unique needs and wants.

For the current circumstances being analyzed, retailers need to comprehend who their customers are and the reason behind picking one channel over the other, in this case, brick-and-mortar over the Internet.

Crawford (2005) finds that the predicament lies in knowing who is buying from a retailer’s brick-and-mortar stores, as it is easy for them to identify their online buyers.

Pookulangra et al. (2011) believe that channel switching can result in channel conflict because a customer can receive service or obtain information from one channel. Still, they may conduct business through another channel.

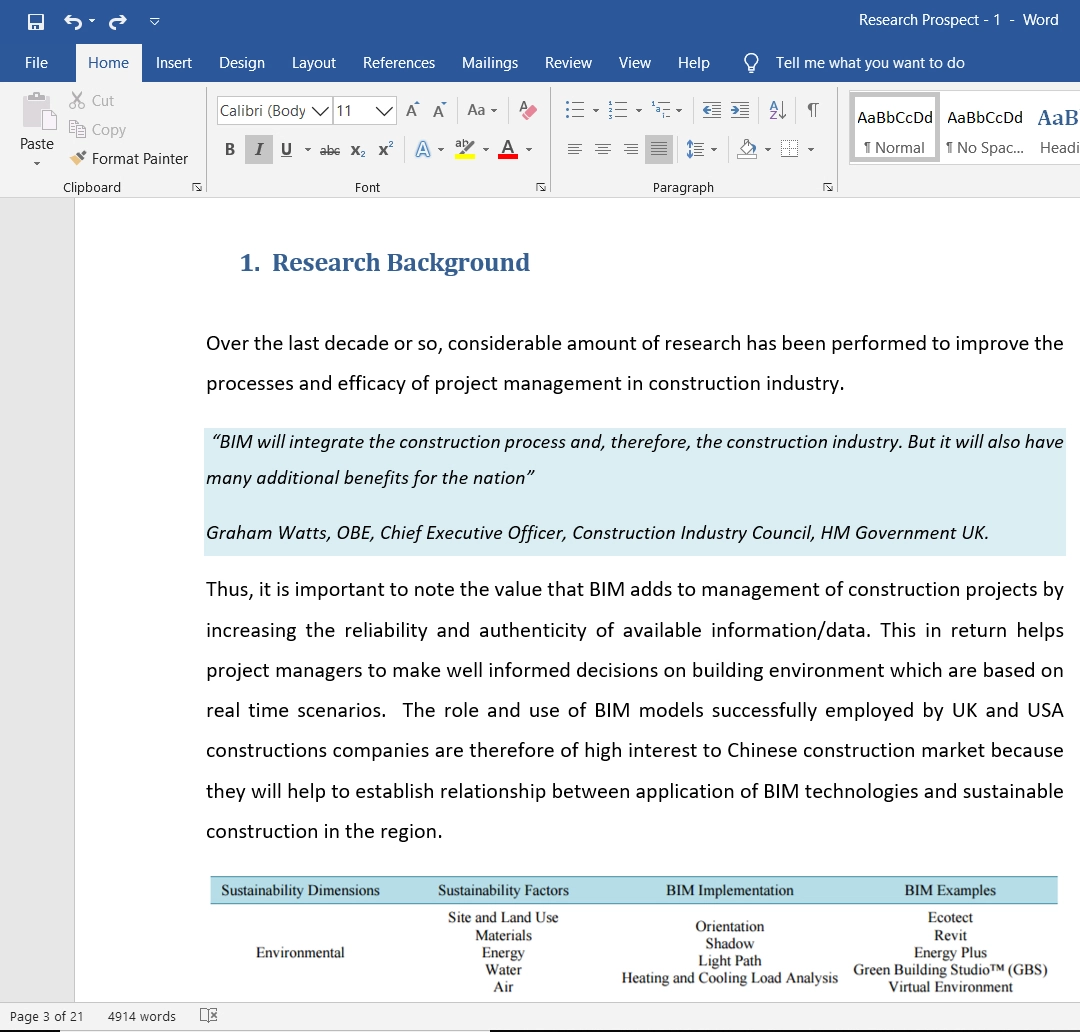

Alba et al. (1997) have identified specific dimensions associated with a retail channel and their impact on attractiveness to a consumer (Table 2.2-1). Alba et al. (1997) argue that specific characteristics available to consumers have different intensities for brick-and-mortar and internet stores, as seen in Table 2.2-1. Based on this table, Internet stores provide consumers with more alternative products than stores and have a high intensity of this dimension.

Kim (2000) compared the shopping values based on hedonic and utilitarian concepts and the perceived behavioural controls of brick-and-mortar stores and the Internet (Table 2.2-2).

The table describes the shopping values categorized on hedonic and utilitarian concepts and behavioural controls for brick and mortar stores and the Internet. Kim (2005) provided these characteristics to explain the behavioural reasons that prompt shoppers to choose a channel. This gives the study characteristics most associated with the specific channel of shopping.

Pookulangra et al. (2011) argue that consumers switch channels based on their beliefs and attitudes concerning each channel in addition to factors such as social norms, perceived behavioural control, and attitude towards channel-switching.

While conducting the literature review, various studies identified consumer channel switching behaviour using traditional and online stores. This section examines these studies using a chronological setup to organize the studies analyzed.

Jarvenpaa and Todd (1997) had found that responsiveness and tangibility had the most significant impact on buying intention during internet shopping, while product perceptions were greater on catalogues than on the Internet.

Madlberger (2006) later replicated Jarvenpaa and Todd’s (1997) study and found that the most important factor influencing consumer attitudes toward online shopping was their catalogs’ attitude.

Madlberger (2006) also found that online shopping convenience resulted in a greater favourable attitude among catalogue shoppers when given a multi-channel retailer’s online store option. This eventually resulted in them preferring online shopping and slowly moving away from catalogue shopping.

Shim et al. (2000) focused their study on examining the impact of the Internet and the traditional retail stores on consumers and their purchase intention. The research had used a sample of 706 participants with no specific user characteristics as they were sampled randomly in the population.

Based on the results Sim et al. (2000) concluded that the Internet was used more for purchasing cognitive products (i.e., products that satisfy users’ needs and desires through cognitive capabilities such as “smart” products). However, the study also found that cross-shoppers were product situation-specific.

Burke (2002) found that shoppers valued different features when they were shopping for other products. The study found that consumers were less interested in using multiple channels when shopping for goods they frequently purchased, like groceries or healthcare products.

Burke (2002) concluded that consumers had valued the option of buying online and picking up the product at the nearest store, also, the option of shopping in the store and having the purchases delivered at home while also being able to return the products to the store or through the mail.

Levin et al. (2003) have used product categories in their study to hypothesize the behaviour of channel switching. Levin et al. (2003) found that products categorized as being “high-touch” like health/grooming merchandise, sporting goods, and clothing products were preferred to be shopped at brick-and-mortar stores.

On the other hand, products categorized as “low-touch” like computer software or airline tickets were preferred to be purchased online because greater importance was placed on shopping quickly.

Gupta et al. (2004) used utility maximization in their study. It was concluded that the utility obtained from online shopping needed to be greater than the utility available under the brick-and-mortar shopping format because it resulted in consumers switching to an online shopping environment.

Gupta et al. (2004) found that channel risk opinions between channels were negatively associated with consumers’ tendency to switch channels.

However, the difference in price-search intent between online and traditional channels positively impacted consumers’ tendency to switch between channels.

Baal and Dach (2005) examined a sample of 489 who made purchases in physical stores and 447 participants who purchased online to understand channel switching behaviours.

The study concluded that the Internet could provide dominant search characteristics, rapid technological changes, and low purchase frequencies.

The study also found that consumers retained cross-channel options when it was more likely to purchase products infrequently. Baal and Dach (2005) also concluded that product characteristics influenced shoppers more when they looked for more information online and then made their purchases in a traditional retail setting.

All the literature reviewed had stringent controls in place to compare their survey results. Also, the literature included above also used quantitative or empirical techniques to analyze and present results. The studies presented above were homogenous in that matter and used surveys as the research instrument.

The fast development of information technologies has provided retailers and other businesses to reach various ends of their operating market (Kollmann & Hensellek 2016).

Over the past decade, more consumers have gained access to the Internet worldwide and have found it convenient and safe to shop online (Segarra et al., 2016). This has led many firms to opt for more eCommerce integration (Powell et al. 2016).

Many internet-enabled business models have also emerged from the information technology boom (Magretta 2002).

One business model that has gained speed is integrating internet channels and the traditional retail channel known through the click-and-mortar business model (Chen et al., 2014).

Many large retails have boomed from just internet sales, such as the revolutionary Amazon.com, built on the clicks-and-order business model (Lim et al., 2005). This section analyses studies that have examined omnichannel models for businesses.

Of the studies reviewed, all were common in that they had set up thorough methodologies by focusing on businesses. Laroche et al. (2005) and Picot-Coupey et al. (2016) had longitudinal case studies as their methodologies.

Using this research approach, the studies were able to analyze companies that had implemented Omni-channels.

Studying the application of Omni-channels helps to understand how characteristics of consumers are implemented to allow businesses to shift from the Internet to traditional retailers. All three pieces of literature produced results with positive impacts of omnichannel implementation.

Studies such as Brynjolfsson et al. (2000) have carried out extensive research to compare businesses online to their traditional brick and mortar counterparts.

The study was conducted over 15 months using a dataset of 8,500 price observations. Brynjolfsson et al. (2000) compared the pricing behaviour at 41 different internet retailers with conventional outlets to study pricing trends.

The study goes on to explore the claim of whether or not the interest has allowed for a frictionless market. The study found that prices on the Internet were about 9-16% lower than those in their conventional outlets (Brynjolfsson & Smith 2000).

However, it was concluded that there was low friction in internet competitions, such as branding and awareness. Still, trust was of greater importance for internet retailers’ trust (Brynjolfsson & Smith 2000).

Laroche et al. (2005) study the intangibility of internet stores in terms of its effect on dimensions of a consumer’s ability to evaluate goods and services; and its perceived risk in conducting the transaction.

This relationship’s purchase environments are mostly explored by comparing purchase environments in conventional stores versus Internet stores. The researchers conducted two experiments to explore this concept.

The first experiment developed a latent model that explores the relationship between evaluation difficulty (ED) and perceived risk (PR). The second experiment explored the effect of the Internet on ED and PR compared to traditional retailers.

Research conducted by Picot-Coupey et al. (2016) aimed to investigate the challenges faced by online retailers when synchronizing clicks with bricks using an omnichannel perspective.

The paper also brought insight into the possible ways to successfully overcome online retailers’ channels to implement an omnichannel strategy successfully. Picot-Coupey et al. (2016) used an in-depth longitudinal case study using French online eyewear retailer Direct Optic from January 2013 to March 2015. The research included 1,500 and more hours of participant observations and 118 interviews (Picot-Coupey et al. 2016)

Ajzen (2001) proposed that planned behaviour theory provides a framework that allows studying attitudes towards behaviours. According to the idea of planned behaviour, the most essential element of an individual’s behaviour is their intent.

For an individual to perform a specific behaviour, a combination of an individual’s attitude toward achieving the behaviour needs to be a combination of an individual’s attitude toward achieving the behaviour. There needs to be the presence of a subjective norm.

An individual’s attitude to a specific behaviour includes subjective norms, normative beliefs, evaluations of behavioural outcomes, motivation to comply, and behaviour beliefs, illustrated in the figure below.

The theory of planned behaviour assumes that behaviour intention is the direct precursor of actual behaviour, as seen in Fig. 2.3-1. For this specific study, the behaviour is defined as the intention to switch shopping channels within the next three months; this includes any form of information searching for a product or buying a product or service.

Also, behavioural intent is defined by the study as a person’s likelihood for engaging in behaviour outlined previously and is a function of the following three components;

1. Attitude (A)

2. Subjective norm (SN)

3. Perceived behavioural control (PBC)

Ajzen and Fishnein (1980) describe behavioural intentions as a summary of motivation needed to perform or conduct a specific behaviour. This also reflects the person’s decision to follow a particular course of action. Lastly, it outlines how hard individuals are willing to perform the specific behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975).

It is evident from the research conducted by Ajzen (1988) that intentions of action can change over time. According to Ajzen (1988), the greater the likelihood of unforeseen events, the greater the chance of change in the intentions.

Based on this premise, the accuracy of a prediction will most likely decline with the amount of time taken between the measurement of intention and observation of the behaviour suspected (Ajzen 1988).

As explained above, the theory of planned behaviour states that a behaviour’s performance is a joint function of intentions and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen 2001).

For an accurate prediction to occur based on the behaviour, it is imperative that the measures of intent, in this case, switch from one channel to another and the perceived behaviour control, are attuned with the behaviour to be predicted.

Ajzen (2002) argues that when people believe that they have the needed resource and opportunities like skills, money, the cooperation of other people, and time; and that specific problems that have a greater chance of coming forth are manageable, people then exhibit confidence in their ability to perform the intended behaviour and also show a high degree of perceived behavioural control.

For the current study, the proposed beliefs that conceive switching shopping channels include self-efficacy and other facilitating conditions, which are hypothesized to impact the channel switching behaviour and use multiple purchasing channels. The model developed for the proposed study takes from Poolulangara et al. (2011) and their study to build upon as seen in Fig. 2.4-2.

Addis and Holbrook (2001) assert that retail characteristics can be identified as either utilitarian or hedonic. According to Lee et al. (2006), functional characteristics offer customers practical functionally, including convenience, price, and assortment.

On the other hand, hedonic characteristics can satisfy the consumer’s emotional wants,s which include atmosphere and social experiences. Based on the classification and understanding of literature, the following hypothesis has been proposed with its negative thesis;

Bandura (1977) defines self-efficacy as individual judgments of an individual’s capabilities to perform a specific behavior; therefore, the stronger the perceived self-efficacy is, the more active the efforts will be.

When applied to the circumstances of channel switching, self-efficacy refers to a customer’s judgment of their capabilities to get product information and buy products from either traditional physical retail stores or through the internet.

Furthermore, facilitating conductions impacts the perceived behaviour control, which sooner or later influences the outcome’s behaviour sooner or later. These variables are known to be in control of the customer and facilitate their behaviour. For this specific model, the facilitating conditions have been termed as information search, time, money, and product type.

Taylor and Todd (1995) argue that the absence of any facilitating conditions represents barriers to switching channels and may inhibit an intention’s development.

Still, the presence of these conditions may not encourage consumers to use channel switching when looking for or buying products. Therefore, according to the research model, the following have been formulated.

Perceived behavioural control is defined as a perception of control but is not considered actual control over the behaviour that is being examined (Notani 1999).

This can be measured by asking direct questions about performing a behaviour or indirectly according to the beliefs about dealing with a specific facilitating or inhibiting factor.

According to Ajzen (2002) and Bansal and Taylor (2002), the more a person believes that they have all the needed resources, abilities, and opportunities to influence behaviour, the more chance they will intend to perform that specific behaviour. Keen et al. (2000) argued that perceived behavioural control acts as a determinant of behaviour. Therefore the following hypotheses have been developed.

The retail industry has drastically changed to become more diversified in the channels in which business is conducted. Because of this, today’s customers are provided with several choices when it comes to retailing, and for them, multiple channels are offered by retailers.

Based on the literature review conducted, various studies have been conducted to understand the channel switching phenomena.

Some diverse characteristics and behaviours influence consumers’ behaviour to switch over channels. By understanding other literature’s conclusions, the current study constructed a conceptual framework to allow the recent research’s build-up. It explained the study’s theoretical basis and built upon a model on which the study revolved around.

Orders completed by our expert writers are

The chapter of the study explains the research philosophies associated with the research to develop an approach implemented to solve the research problem. The chapter provides a detailed discussion of how the research method was conducted using specific data collection and analysis strategies.

The following sections describe the philosophical and interpretive stances of the current study. It is based on these premises that the entire methodology of the current study was developed.

In order for the current study to be defendable, these assumptions and approaches were essential.

The way research is conducted can be developed in terms of the research philosophy used and the research strategy employed. Therefore, the produces a set of research instruments that can be incorporated to achieve the research objectives (Fig. 3.2-1).

There are many ways to customize research approaches to develop a strategy most suited for a particular study. However, the main three categories of organized research approaches include; qualitative, quantitative, and mixed research methods. Creswall (2013) comments that all three approaches are not considered discrete or distinct.

Creswall (2013) states, “qualitative and quantitative approaches should not be viewed as rigid, distinct categories, polar opposite, or dichotomies” (p.32).

Newmand and Benz (1998) pointed out that quantitative and qualitative approaches represent different ends on a continuum since a study “tends” to be more quantitative than qualitative or vice versa.

Lastly, mixed methods research resides in the middle of the continuum as it can incorporate elements and characteristics of both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Lewis (2015) points out that the main distinction that is often cited between quantitative and qualitative research is that it is framed using numbers rather than words; or using closed-ended questions for quantitative hypotheses over open-ended questions for qualitative interview questions.

Guetterman (2015) points out that a clearer way of viewing gradations of differences between the approaches is to examine the basic philosophical assumptions brought to the study, the kinds of research strategies used, and the particular methods implemented in conducting the strategy.

To construct the current study methodology, it is essential to establish a set of beliefs or principles that will act as the current study’s guiding route. For this reason, various philosophical research assumptions were examined to choose one which fits the current study in terms of providing it with a foundation.

Research philosophy believes how data about a phenomenon or situation should be gathered, analyzed, and used. According to Galliers (1991), the two major research philosophies that have been identified in the Western tradition of science are positivist and interpretivist.

Positivism reflects the acceptance of adopting the philosophical stance of natural scientists (Saunders, 2003). According to Remenyi et al. (1998), there is a greater preference in working with an “observable social reality” and that the outcome of such research can be “law-like” generalizations that are the same as those which physical and natural scientists produce.

Gill and Johnson (1997) add that it will also emphasize a highly structured methodology to replicate other studies. Dumke (2002) agrees and explains that a positivist philosophical assumption produces highly structured methods and allows for generalization and quantification of objectives that statistical methods can evaluate.

For this philosophical approach, the researcher is considered an objective observer who should not be impacted by or impact the research subject.

An in-depth study of both these positions has resulted in the current study choosing the positivist approach for becoming the philosophical basis of the current research. Positivist philosophy believes that reality is stable and can be observed and described from an objective viewpoint (Galliers 1991; Levin 1988).

This can be achieved even without interfering with the phenomena that are under study. The premise held by the thought is that the phenomena should be isolated and that observations should be repeatable.

Levin (1988) contends that this involved manipulating reality with variations of only a single independent variable to identify regularities to construct relationships between them.

The positivist viewpoint is a scientific viewpoint that allows one to evaluate theory using substantial evidence that can be obtained again using a rigid research method that can be replicated. It is for this reason that the positivist assumptions make up the foundation of the current study.

Using the philosophical assumptions made in the previous section, the interpretive research selection is made as to the deductive approach. The main purpose of a deductive approach is to be aimed at and tested towards theory (Babbie 2010).

The approach begins with a hypothesis (Fig. 3.2-2), unlike the inductive approach, which is concerned with generating new theory from emerging data while using research questions to narrow the study’s scope (Wilson 2010).

The deductive approach places a greater emphasis on causality. Gulati (2009) argues that the deductive approach follows logic the most closely with reasoning starting with theory and leading to a new hypothesis.

Babbie (2010) defines quantitative research methods as placing a greater emphasis on objective measurements and “the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques.”

This basically means that quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and then generalizing it across many groups of people or even explaining a specific phenomenon that was the focus of the study (Wilson 2010).

The quantitative research approach is best suited for the current study because of this reason. The study’s goal is to conduct quantitative research to determine a relationship between consumer choices of shopping channels on a business’s decision to shift to brick-and-mortar stores within the UK population.

Through quantitative research, the data obtained and projected can generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or even investigate causal relationships. (Gulati 2009).

Many research strategies can be used, which include field experiments, laboratory experiments, simulation, case studies, reviews, surveys, and interviews, to name a few. However, a study’s right strategy depends on the underlying assumptions made from the philosophical and interpretive premises developed.

The current study looks to follow a quantitative research approach by using positivism and deductive reasoning. For this reason, a survey was considered the best strategy. The choice of this is also in parallel to the steps presented in a typical ‘research onion’ (see Fig 3.4-1)

With the underlying theme of positivist and deductive reasoning, available research strategies that will allow the research objectives can only survey.

Surveys enable researchers to obtain data about practices, situations, or viewpoints at a single point in time through questionnaires. Through the use of quantitative analytical methods, the data is manipulated to draw inferences regarding existing relationships.

Through the use of surveys, a researcher can study more variables at a single time than the option of laboratory tests or field experiments. With surveys, this all becomes possible while data is still being collected within real-world environments.

The study is based completely on a quantitative research design composed using the scientific method indicated as the hypothetico-deductive method. Kuhn (2012) finds that the quantitative research approach allows for the interpretation of observations for the sole reason of discovering an underlying meaning or patterns of a relationship, which also means the ability to classify phenomena in a way that involves mathematical models. The sections that follow present the important components that make up the research design.

For the current study, a questionnaire was developed, which was to be self-administered to consumers. The questionnaire consists of items that can measure the beliefs towards switching channels using hedonic and utilitarian beliefs and attitudes towards switching channels between the internet and brick and mortar stores.

The questionnaire can measure perceived self-efficacy, facilitating conditions set as time, money, information and production type, and perceived behavioral control for the internet to brick and mortar.

The questionnaire also included information that collected answers on the respondents’ demographics, including age, marital status, gender, work status, annual household income, ethnicity, number of children, and education.

The variables under attitude beliefs, self-efficacy, time, money, product type, and information are associated with outcomes per the expectancy-value model. The survey is presented in Appendix A.

The survey is made of Likert-like items using a 7 point scale that gives varying degrees of expression for each statement.

The sample of the study was chosen based on random sampling. No specific requirements were placed on obtaining a sample, and the population chosen was anyone who purchased products or services using the internet and/or brick-and-mortar stores.

A total of 300 respondents is intended to be collected to ensure a wide range of perspectives. The sample was obtained by posting the survey online for seventy days to ensure that a maximum number of people responded to reach the desired sample size value of 300.

The data analysis will be analyzed using IBM SPSS v. 24 for descriptive analysis, factor analysis, and regression analysis. Each of the tools used for data analysis will be used according to the section on the survey.

Firstly, the demographic section of the survey will be analyzed using frequency statistics. A further frequency analysis will be conducted on questionnaire section II in addition to a reliability test using Cronbach’s alpha.

However, both simple and multiple regression will be used for complete data analysis. The premise set for such analysis is that the dependent variables were independent variables for the next stage of the model.

One of the primary issues for data collection was distributing the survey online using Survey Monkey. The issue with this is the lack of response rate, which cannot be calculated as the researcher will not know how many individuals had seen the survey and chose not to participate. This is one of the major drawbacks of online distribution.

Another drawback is ensuring that the survey was taken once by a single person and not taken multiple times by a single person. However, it is assumed for the sack of the study that individuals completed the survey once.

This Internet use was only chosen due to lack of funds and time limitation in completing the entire study.

The current chapter has outlined the crucial components that make up the methods of the research. It is through these methods that the research aims and objectives will be accomplished.

The chapter provides an in-depth discussion of the current study’s underlying philosophy, interpretive beliefs, and research approach. Using these components, the study has set up a research design that can be replicated and produces results, as discussed in the next chapter.

The chapter presents the findings of the study. The questionnaire acquired the data (see Appendix A) and analyzed using IBM SPSS v. 24. The data was analyzed for descriptive, Cronbach’s alpha, and regression analysis.

The frequency statistics were acquired for the demographic analysis of the sample. As mentioned earlier, the data was collected through random sampling by placing the survey on the Internet using Survey Monkey.

The primary issue with this was that there is no specific population representation and the population being questioned is unknown. As with all surveys, there are chances of respondent bias, resulting in the interaction between variables and outliers in the data.

The first section of the chapter describes the demographics, followed by a frequency analysis of section II questions, Cronbach’s alpha, and regression analysis.

The proposed sample designated for the current study was 300. The survey was posted on the Internet for seventy days to allow the maximum number of respondents to answer them.

However, a total of 243 completed surveys were received within the seventh-day period. Only surveys that were filled were included in the data analysis. Based on the surveys’ demographic analysis, a total of 107 males participated while 136 females participated.

Table. 4.2-1 illustrates the respondents’ ethnicity; from the data obtained, 71 Hispanics had participated in the survey, making them the largest group examined in terms of ethnicity compared to other ethnicities.

The smallest group present in respondents identified as Caucasians, with only 15 participants present in the sample. Other characteristics of the respondents in the current study are present in Table 4.2-2 below.

Based on the table presented, 103 individuals made up the largest group of respondents based on age in the 24-40-year-old category. On the other hand, only 36 participants were representative of individuals above 55 years old.

The median age for the participants was ages 25-40 years old. Of the sample, 98 participants held a Bachelors, and only one participant had no education. The median response for education was also bachelors, as present in Table 4.2-3.

Based on the income, a majority of respondents (82) indicated that they earned £8,000 to £24,999 annually; while only seven indicated that income annually was £57,000-£72,999.

The median response for annual income among respondents was £8,000- £24,999. An equal number of respondents indicated that they worked part-time and full time, split 86 participants indicating this.

However, only 71 respondents indicated that they did not work. Based on the frequency analysis, the median response was working full time. The marital status of 105 participants was either married or living with a partner, while only 76 were separated/widowed/divorced. The median answer of respondents was also married/living with a partner.

Table 4.3-1 explains the descriptive statistics of brick and mortar stores, catalogue, and internet usage for finding information on products and purchasing products in the last three months.

About 91% of participants indicated that they searched for product information in stores, followed by about 51% of searches using catalogues. Most participants stated that they searched for information on the Internet, about 96%.

Also, participants indicated that 97% of them purchased products in the last three months from stores, while an estimate of 46% purchased from catalogues, and about 99% purchased online.

The questionnaire section II was designed using Likert-like questions that respondents were asked to answer using a seven (7) point scale. Results of the questionnaire using cumulative percentage frequency are presented in Figs 4.3-1. below.

Fig. 4.3-1 presents the questionnaire results that analyzed hedonic and utilitarian beliefs; variables of self-efficacy, time, money, information hedonic products, utilitarian products; outcomes of self-efficacy; and behavioural intention.

The results show that 51.9% of respondents agreed to some degree that changing from the Internet to stores while shopping was fun. About 55% of respondents also indicated some agreement level that changing from the Internet to stores when shopping was enjoyable.

For utilitarian beliefs present in question 3g, respondents presented a large majority with about 75% in some degree of agreement changing from the Internet to stores when shopping is efficient.

Questions 6d to 6h analyzed self-efficacy variables, time, money, information hedonic products, and utilitarian products. Based on the results presented in the figure below, 51.9% of respondents indicated some agreement level that they had the time to change between stores and the Internet.

Question 6f illustrates that about 58% of respondents agreed that they had the information needed to change between stores and the Internet to varying degrees. This supports the prediction made in hypothesis 5 that information will predict the perceived behavioural control when switching from the Internet to brick-and-mortar stores.

Reliability of items is necessary for evaluating assessments and questionnaires (Tavakol and Dennick 2011). It is often thought of as mandatory in research to estimate the quantity of alpha to increase the validity and accuracy of interpretations of results for a given data set.

Academics such as Gliem and Gliem (2003) argue that it is important to calculate Cronbach’s alpha when using Likert-type scales used in the current study. Using SPSS, the following figure below presents the result for Cronbach alpha.

Kline (2000); Georgy and Mallery (2003); and DeVeillis (2012) provide the following rules for identifying internal consistency; α ≥ 0.9 – excellent; 0.9 ≥ α ≥ 0.8- good; 0.8 ≥ α ≥ 0.7- acceptable; 0.7 ≥ α ≥ 0.6 questionable; 0.6 ≥ α ≥ 0.5- poor; and 0.5 ≥ α- unacceptable.

The alpha produced for the current study is .924, making it reside in the excellent category.

Thus, it is concluded that the questionnaire produced with all its items holds a fair internal consistency making the items in the study’s questionnaire measured as one-dimensional.

Other uninformed values of variables in the analysis produced closeness in the value of alpha presented in Appendix B. This proves that the study’s alpha is not deflated or inflated by external or internal factors.

The section discusses the regression analysis for channel switching behaviour from the Internet to brick-and-mortar stores. For the analysis, independent variables used to predict channel switching behaviour attitudes were hedonic and utilitarian beliefs toward the Internet to store behaviour, the dependent variable.

The R2 value presented in the analysis increases once new terms are introduced into the regression model. Meaning, the addition of variables like hedonic beliefs, utilitarian beliefs, time, self-efficacy, normative beliefs, hedonic & utilitarian products, money, and information. All of these were independent predictor variables that were hypothesized to influence channel switching behaviour.

The significant predictor of the dependent variable was Utilitarian beliefs with a regression coefficient of 0.385 (p<.001) accompanied by an overall F value of 72.233 (p<.001) and an Adjusted R2 value of 0.18.

Therefore, the results support hypothesis H2 that utilitarian beliefs will significantly predict switching between the Internet to brick and mortar stores.

Other variables such as self-efficacy, time, money, information, hedonic products, and utilitarian products were kept independent of predicting the participants’ perceived behavioural control (PBC).

Based on the results of the regression analysis majority of contributing factors the significantly predicted the dependent variable were self-efficacy with values at 0.173 (p<.001) and information valued at 0.429 (p<.001), as seen in Table 4.3-3.

These values were accompanied by an overall F value of 72.724 (p<0.001) and an adjusted R2 value of 0.43. Using the stepwise regression analysis method for predicting perceived behavioural control (PBC) changed the value of adjusted R2 to 0.41 and increased F’s value to 152.148 (Table 4.3-3).

Significant predictors of PBC based on this method were self-efficacy with 0.179 (p<.001), information at 0.421 (p<.001), and Utilitarian products producing 0.184 (p<.05).

Based on these results, hypotheses H3, H5, and H8 are supported. Self-efficacy, information, and utilitarian products will predict the perceived behavioural control when switching from the Internet to brick-and-mortar stores.

Furthermore, PBC was set as an independent variable to predict channel-switching behaviour. Table 4.3-4 illustrates that PBC significantly influences channel switching behaviour with 0.113 (p<.001) with an adjusted R2 of 0.05 and F of 34.245.

This supports hypothesis H9. Variables of attitude and PBC were kept as independent variables for the dependent variable channel switching intention.

Table 4:3-4 illustrates attitude with 0.359 and PBC -0.092 with an adjusted R2 of 0.49 and F of 179.012. These results support hypothesis H10. Lastly, channel-switching intention significantly predicted channel switching behavior with produced regression value of 0.276 (p<.001) with an adjusted R2 or 0.06 and F value of 37.454.

Table 4.3-3: Regression Analysis of Additional Variables

Table 4.3-4: Regression Analysis of Channel Switching Behaviour

Based on the study’s findings, variables of Utilitarian beliefs, self-efficacy, information, utilitarian products, and attitude are significantly contributing factors for prompting customers to switch from using the Internet as a purchasing and information searching channel to brick and mortar stores.

These factors are concluded as the customers are looking more towards using brick-and-mortar stores than capping online, writing businesses to establish physical store locations to accommodate customers. The findings were analyzed using frequency analysis, Cronbach’s alpha analysis, and regression analysis.

The research had looked to answer the research question;

How has consumer behavior influenced the shift of click-and-order stores to more traditional retailing with physical stores?

Using the Theory of Planned Behavior, the research question was analyzed using a quantitative research approach. The approach included using a quantitative research instrument, in this case, a questionnaire tool to examine behaviour in participants. A total of 300 participants were proposed to partake in the study.

However, only 243 valid, fully completed questionnaires were acquired using Survey Monkey, an online survey tool. The data were analyzed using frequency analysis and regression analysis to examine how certain variables may influence channel switching behaviour among consumers by acquiring data through this route.

Based on the conducted study, analyzing how consumers have influenced businesses to shift to traditional retailing using the Theory of Planned Behaviour was achieved. The theory had assumed that individual attitudes and beliefs and control factors would result in an intention to perform a behaviour, switching from online shopping to using physical stores.

The research objectives were to highlight the various pros and cons of business models on clicks and bricks, achieved in the Literature Review Chapter 2. The literature review also achieved the literature review also achieved the investigation of the impact that online stores have on consumers and the retail industry.

The objective of exploring factors that influence aconsumer’ss decision toconsumer’som online to shopping in physical stores was achieved by the experimental investigation using the questionnaire and present in the results of chapter 4. The results of the study concluded that the following hypotheses were found supported by the data:

H2: Utilitarian beliefs will predict attitude towards switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

H3: Self-efficacy predicts the perceived behavioural control when switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

H5: Information will predict the perceived behavioural control when switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

H8: Utilitarian products will predict the perceived behavioural control when switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

H10: Attitude directed towards channel switching will predict channel switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

H11: PCB directed towards channel switching will predict switching from the internet to brick and mortar stores.

Overall the current study successfully predicted a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables presented in the theory of planned behaviour research model for channel switching from internet to brick and mortar stores.

The findings of the current study will have implications on the retail industry looking to develop an omnichannel business model for more informed consumers.

The information presented in the current study will also aid and impact researchers looking to divulge a depth study on variables that provide greater insight in switching from the internet to physical stores.

Most importantly, the current study results impact retailers in the UK due to the interactions between variables. This will allow retailers to shift to physical stores a body of knowledge of combining specific variables that will produce the desired outcome from consumer behaviour. According to Reardon and McCorkle (2002), managing several sales channels actively requires knowing its channel preference.

The findings of the current study cannot be generalized to the population analyzed in the study because the samples obtained were not normally distributed specifically regarding the characteristics found in the demographics of participants.

The respondents’ characteristics shorespondents’45% of partrespondents’e between 25 to 40 years old. There was also a predominance of Hispanic and married participants compared to other ethnic groups and marital statuses.

It is recommended that studies in the future ensure a large amount of sample size to ensure more diversity in participant characteristics. It is also recommended that future studies indulge in further analysis by separating different sample groups to provide more robust information for retailers.

There was difficulty in calculating the response rate since the survey was administered online. Kaye and Johnson (1999) argue that web-based surveys cannot calculate their response rates since there is no way of knowing how many individuals might have seen the survey link but declined to participate in the study. It is recommended that future studies use more than one method to administer surveys to ensure maximum participation and analysis.

Addis, M. & Holbrook, M. B. 2001. On the conceptual link between mass customization and experiential consumption: An explosion of subjectivity. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 1(1), 50-66.

Alba, J. W, & Hutchison, J. W. 1987. Dimensions of consumer expertise. The Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 411-454.

Ajzen, I. 1988. Attitudes, personalities, and behaviour. Chicago, IL: Dorsey

Ajzen, I. 2001. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 27-58.

Ajzen, I. 2002. Perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy, locus of control and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665-683.

Ajzen, I, Brown, T. C., & Carvajal, F. 2004. Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: The case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(9), 1108-1121.

Ajzen, I, & Driver, B. L. 1992. Application of the theory of planned behaviour to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24(3), 207-224.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Baal, S., & Dach, C. 2005. Freeriding and consumer retention across retailers’ channels. Journal of Interactive Marketinretailers’75-85.

Banduretailers’7. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bansal, H. S., & Taylor, S. F. 2002. Investigating interactive effects in the theory of planned behaviour in a service-provider switching context.

Psychology & Marketing, 19(5), 407–425.

Balasubramanian, S, Raghunathan, R., & Mahajan, V. 2005. Consumers in a multichannel environment: Product utility, process utility, and channel choice. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(2), 12 – 30.

Bandura, A. 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147.

Page 47 of 67

Bernstein, F., Song, J. S., and Zheng, X. 2008. Bricks-and-mortar vs clicks-and-mortar: an equilibrium analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, pp. 28-56.

Brynjolfsson, E. & Smith, M.D., 2000. Frictionless Commerce? A Comparison of Internet and Conventional Retailers. Management Science, 46(4), pp.563–585.

Burke, R. R. 2002. Technology and the consumer interface: What consumers want in the physical and virtual store. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(4), 411-32.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Chen, S.-L., Chen, Y.-Y. & Hsu, C., 2014. A new approach to integrate Internet-of-things and software-as-a-service model for logistic systems: a case study. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 14(4), pp.6144–6164.

Crawford, J. (2005). Are you measuring your multichannel consumer experience? Apparel, 47(4), S1-S8.

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley,

Glanz, K., Bader, M.D.M. & Iyer, S., 2012. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(5), pp.503–512.

Gupta, A., Su, B., & Walter, Z. 2004. An empirical study of consumer switching from traditional to electronic channels: A purchase-decision process perspective. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8(3), 131–161

Hoisington, A. et al., 2015. Characterizing the Bacterial Communities in Retail Stores in the United States. Indoor Air.

Jarvenpaa, S. L. & Todd, P. A. 1997. Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the World Wide Web. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 1(2), 59-88.

Johnson, J. L. 1999. Face to face… with Sid Doolittle. Discount Merchandiser, 39(5), 14-17.

Keen, C, Wetzels, M., Ruyter, K., & Feinberg, R. 2004. E-Tailers versus retailers. Which factors determine consumers preferences. Journal of Business Research, 57(7), 685-95.

Kim, H-S. 2005. Using hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations to profile inner-city consumers. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 13(1), 57-79

Kollmann, T. & Hensellek, S., 2016. The E-Business Model Generator. In I. Lee, ed. Encyclopedia of E-Commerce Development, Implementation, and Management. IGI Global, pp. 26–36.

Kurt Salmon Associates. 2005. Multichannel retailing: Exponential opportunity- insight, information, and profits. [online] h<ttp://www.kurtsalmon.com> [Accessed: 12th December 2016].

Laroche, M. et al., 2005. Internet versus bricks-and-mortar retailers: An investigation into intangibility and its consequences. Journal of Retailing, 81(4), pp.251–267.

Lee, M-Y, Atkins, K. G., Kim, Y-K, & Park, S-H. 2006. Competitive analyses between regional malls and big-box retailers: A competitive analysis for segmentation and positioning. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 13(1), 81-98.

Levin, A. M., Levin, I. P., & Heath, C. E. 2003. Product category dependent preferences for online and offline shopping features and their influence on the multichannel retail alliance. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 4(3), 85-93.

Lim, H. & Dubinsky, A. J. 2005. Determinants of consumers’ purchase intention on the Internet: An appliconsumers’the theory ofconsumers’ehaviour. Psychology & Marketing, 22(10), 833-855.

Magretta, J., 2002. Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), pp.86–92, 133.

Madlberger, M. 2006. Exogenous and endogenous antecedents of online shopping in a multichannel environment: Evidence from a catalogue retailer in the German-speaking world. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 4(4), pp.29-51.

Molina-Azorin, J.F., 2016. Mixed methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25(2), pp.37–38.

Molina-Azorin, J.F. & Fetters, M.D., 2016. Mixed Methods Research Prevalence Studies: Field-Specific Studies on the State of the Art of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of mixed methods research, 10(2), pp.123–128.

Notani, A. S. 1998. Moderators of perceived behavioural control’s predictiveness in the theory of plancontrol’siour: A meta-acontrol’sJournal of Consumer Psychology, 7(3), 247-271.

Picot-Coupey, K., Huré, E. & Piveteau, L., 2016. Channel design to enrich customers’ shopping experiences. Internationacustomers’of Retail &amcustomers’ution Management, 44(3), pp.336–368.

Poolulangara, S., Hawley, J., Xiao, G. 2011. Explaining consumers’ channel switching behaviour using consumers’planned behavconsumers’nal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 10(1), pp. 122-146.

Powell, W.W., Horvath, A. & Brandtner, C., 2016. Click and mortar: Organizations on the web—research in Organizational Behavior.

Prince, D.B. & Graf, T., 2015. Geisinger’s Retail Innovation Journey. FrontiGeisinger’sth services Geisinger’s 31(3), pp.16–31.

Rangaswamy, A. & Bruggen, G. V. (2005). Opportunities and challenges in multichannel marketing: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(2), 5-11.

Reardon, J., and McCorkle, D. E. 2002. A consumer model for channel switching behaviour. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 30(4), pp. 179-185.

Schneir, A. et al., 2014. Comprehensive analysis of “bath salts” purchased from California stores”and the in”ernet. Clin”cal Toxico”ogy, 52(7), pp.651–658.

Segarra, L.L. et al., 2016. A Framework for Boosting Revenue Incorporating Big Data. Journal of Innovation Management. Available at: http://www.open-jim.org/article/view/160.

Seth, J. N. & Sisodia, R. S. 1997. Consumer behaviour in the future. In Robert A. Peterson (Ed.), Electronic Marketing and the Consumer (pp. 17-37). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shim, S., Eastlick, M. A., & Lotz, S. (2000). Assessing the impact of Internet shopping on store shopping among mall shoppers and Internet users. Journal of Shopping Center Research 7(2), 7-44.

Sullivan, U. Y. & Thomas, J. S. (2004). Consumer migration: An empirical investigation across multiple channels. Working Papers 0112.

Taylor, S, & Todd, P. 1995. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behaviour: A study of consumer adoption intentions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12, 137-155

Walsh, A. 2016. Amazon Go store lets shoppers pick up goods and walk out. The Guardian, [onlin] < https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/dec/05/amazon-go-store-seattle-checkouts-account>[Accessed: 15th January 2017].

About You: The following are background information questions included to help interpret the reason for your responses regarding the questions of the succeeding sections. Your responses in this section and all sections of the questionnaire will the kept strictly confidential.

1. Indicate your gender.

o Male o Female

2. Indicate your age group.

o 18-25 o 25-40 o 40-55 o Above 55 years old

3. Please indicate the highest level of education that you have acquired.

o Primary Education o GCSE/O-level o CGE/A-level o Bachelors o Graduate o Doctoral o None

4. Are you working?

o No o Part-time o Full Time

5. What is your marital status?

o Single/Never married o Married/living with partner o Separated/widowed/divorced

6. Which of the following best describes your ethnicity?

o African o Asian o Caucasian o Hispanic o Other

7. What is your annual household income from all sources before taxes?

o Less than 8,000 o 8,000- 24,999 o 25,000- 40,999 o 41,000- 56,999 o 57,000-72,999 o 73,000 or more

8. Please fill in the number of children dependent on you for each category.

None Under 6 years old 6 to 12 years old 13 to 17 years old 18 years and/or older

Section II-

Please read each of the statements and follow the instructions for answering each of these statements.

1. Have you ever in the past year searching for information about goods or services from any of the following in the last three months? (Tick all that apply)

Store Catalog Internet

2. Have you ever made a purchase of goods or services from any of the following in the last three months? (Tick all that apply)

Store Catalog Internet

Please read each statement and circle the answer that indicates your opinion.

3. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements when “changing from the internet to stores when shopping.” Circle that number that best describes your opinion.

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. It is fun (b1i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| b. It is enjoyable (b2i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| c. The shopping experiencing truly feels satisfying(b3i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| d. It is rewarding (b4i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| e. It is convenient (b5i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| f. It is easy (b6i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| g. It is efficient (b7i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

5. How do you feel for each of the following when “changing from the internet to store while shopping.” Circle that number that best describes your opinion.

| a. The idea of using a store instead of the internet (a1i) |

Dislike -3 | Neutral 0 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Like 3 |

| b. Enjoyment is (e2i) | Foolish -3 | -2 | -1 | Neutral 0 | 1 | 2 | Wise 3 |

| c. Having a satisfying experience is (e3i) |

Bad -3 | -2 | -1 | Neutral 0 | 1 | 2 | Good 3 |

| d. Having a rewarding experience is (e4i) |

Bad -3 | -2 | -1 | Neutral 0 | 1 | 2 | Good 3 |

6. How much do you agree with each of the following statements concerning “changing from the internet to store while shopping”?

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. If I wanted to, I could change between stores and internet on my own. (cb1i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| b. I know enough to change between stores and the internet on my own. (cb2i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| c. I would feel comfortable changing between stores and the internet on my own. (cb3i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| d. I have the time needed to change between stores and the internet. (cb4i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| e. I have the money to change between stores and internet. (cb5i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| f. I have the information needed to change between stores and the internet. (cb6i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| g. I have the ability to buy products such as apparel, jewelry, flowers, and home furnishings. (cb7i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| h. I have the ability to buy products such as travel, financial services (tax returns, stocks, home banking, and credit card) (cb8i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| i. I have the resources, knowledge and ability to change between stores and internet. (PBC1i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| j. I would be able to change between stores and internet (PBC2i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

7. How much do you agree with each of the following statements concerning “changing from the internet to store while shopping”?

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Being able to change between stores and internet on my own. (pf1i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| b. Knowing enough to change between stores and the internet. (pf2i) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| c. Being comfortable changing between stores and the internet on my own. (pf3i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| d. Having the time needed to change between stores and internet. (pf4i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| e. Having the money needed to change between stores and internet. (pf5i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| f. Having the information needed to change between stores and internet. (pf6i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| g. Having the ability to buy a production such as apparel, jewelry, flowers, and home furnishings. (pf7i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| h. Having the ability to buy products such as travel and financial services. (pf8i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

8. Please answer the following regarding the overall intention to “changing from the internet to stores while shopping.”

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. I intend to change to store from the internet while shopping. (bi1i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| b. I plan to change to store from the internet for all my shopping. (bi2i) |

-3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

9. Please answer the following concerning the overall actual behavior of “changing between the Internet and stores.”

| a. How many times in the last three months have you changed from the internet to a store while searching for information? | Never | 1-5 times | 6-10 times | 11-15 times | >15 times |

| b. How many times in the last three months have you changed from the internet to a store while purchasing? | Never | 1-5 times | 6-10 times | 11-15 times | >15 times |

| c. How many times in the last three months have you changed from store to internet while searching for information? | Never | 1-5 times | 6-10 times | 11-15 times | >15 times |

| d. How many times in the course of the last three months have changed from store to internet while purchasing? |

Never | 1-5 times | 6-10 times | 11-15 times | >15 times |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| b1i | .1070 | 2.10000 | 243 |

| b2i | .5144 | 2.03756 | 243 |

| b3i | .6749 | 1.83550 | 243 |

| b4i | .5432 | 2.08328 | 243 |

| b5i | 1.4897 | 2.68507 | 243 |

| b6i | 1.2922 | 1.44636 | 243 |

| b7i | 1.2675 | 1.37812 | 243 |

| e1i | 1.2840 | 1.75975 | 243 |

| e2i | 1.2263 | 1.72314 | 243 |

| e3i | 1.0741 | 1.70641 | 243 |

| e4i | 1.64225 | 243 | |

| e5i | 1.2675 | 1.62574 | 243 |

| e6i | 1.1934 | 1.64883 | 243 |

| e7i | 1.0288 | 1.85730 | 243 |

| a1i | .7160 | 1.92140 | 243 |

| a2i | .5885 | 1.86402 | 243 |

| e5i | 1.2675 | 1.62574 | 243 |

| e6i | 1.1934 | 1.64883 | 243 |

| e7i | 1.0288 | 1.85730 | 243 |

| b1i | .1070 | 2.10000 | 243 |

| b2i | .5144 | 2.03756 | 243 |

| b3i | .6749 | 1.83550 | 243 |

| b4i | .5432 | 2.08328 | 243 |

| b5i | 1.4897 | 2.68507 | 243 |

| e4i | 1.64225 | 243 | |

| e5i | 1.2675 | 1.62574 | 243 |

| e6i | 1.1934 | 1.64883 | 243 |

| b5i | 1.4897 | 2.68507 | 243 |

| b6i | 1.2922 | 1.44636 | 243 |

| b7i | 1.2675 | 1.37812 | 243 |

| e1i | 1.2840 | 1.75975 | 243 |

| e4i | 1.64225 | 243 | |

| e5i | 1.2675 | 1.62574 | 243 |

| e6i | 1.1934 | 1.64883 | 243 |

| b5i | 1.4897 | 2.68507 | 243 |

| b6i | 1.2922 | 1.44636 | 243 |

| Searching Internet to Store | 3.1152 | .96803 | 243 |

| Purchasing Internet to Store | 3.5844 | .92491 | 243 |

| Searching Store to Internet | 2.1687 | .76624 | 243 |

| Purchasing Store to internet | 1.9506 | .73869 | 243 |

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 18 – 25 | 48 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 19.8 |

| 25 – 40 | 48 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 19.8 | |

| 40 – 55 | 48 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 19.8 | |

| Above 55 years old | 48 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 19.8 | |

| Total | 243 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 5.4-2: Frequency Analysis of Education

Table 5.4-3: Frequency Analysis of Working Hours

Table 5.4-4: Frequency Analysis of Marital Status

Table 5.4-5: Frequency Analysis of Ethnic Group

Table 5.4-1: Reliability Analysis of Questionnaire using Skewness and Kurtosis

Table 5.4-1: Regression Analysis Results Presentation of Correlations

The time required to write a master’s level full dissertation varies, but it typically takes 6-12 months, depending on research complexity and individual pace.