Disclaimer: This is not a sample of our professional work. A student has produced the paper. You can view examples of our work here. Opinions, suggestions, recommendations, and results in this piece are those of the author and should not be taken as our company views.

Type of Academic Paper -Assignment

Academic Subject – Law of International Trade

Word Count – 6000 words

INCOTERMS 2010 refers to the latest collection of essential international commercial and trade terms. These specific terms were formulated for the acknowledgment of non-uniform standard trade usages amongst the various states involved. INCOTERMS code provides a detailed interpretation of rights and obligations between parties when integrated into a sale contract. In most jurisdictions, any given INCOTERMS will not be integrated into a contract without its expressed or implied reference to it becoming an INCOTERM. The INCOTERMS 2000 have been classified into four different classes which are the following:

The two new rules; DAP & DAT have been introduced in the revised 2010 version reducing the thirteen rules in INCOTERMs to eleven by replacing the previous version (DAF, DES, DEQ,& DDU). However, the revised eleven terms of INCOTERMs 2010 have subdivided the rules into two categories based only on the method of delivery: (i) Terms for any transport Mode & (ii) Maritime- only terms. For this paper, six of the rules will be identified, analysed, and outlined, which are:

Module- Law of International Trade

Each of the INCOTERMs rules varies according to the sellers’ and the buyers’ obligations, which will be analysed in-depth in the following sections. Briefly, the three chosen rule’s differences will be identified.

For the FCA (Freed Carrier), the rule is categorised under the named place of delivery. Under this rule, the Seller delivers the goods that are cleared for export to the carrier that is selected by the Buyer. The Seller’s responsibility is to load the goods if the carrier pickup is at the Seller’s premises. From this specific point, the Buyer is obligated to bear the costs and the risks of moving the goods to the desired destination.

The next rule, DAP (Delivered at Place) is categorised as the named place of destination. This rule highlights that the Seller is the one that delivers when the goods are placed at the Buyer’s disposal on the arriving means of transport which is ready for unloading at the named place of destination. With this rule of INCOTERM, the Seller is the one that bears all the risks that are involved in bringing the goods to the named place.

Lastly, the CIF rule (Cost Insurance and Freight) is categorised under the named port of destination. Under this rule, the seller clears the goods for export and pays the costs of moving the goods to the destination port. The Buyer is the one that bears all the risks of loss or damage. However, the Seller is the one that purchases the cargo insurance.

Each of the rules of INCOTERMs that are being analysed has a lot of differences that need to be considered before agreeing to a certain rule to incorporate in the contract between the Buyer and the Seller. Each of the rules explains the obligations that each party has under the specified terms of that rule. This portion will attempt to analyse the differences found in each contract rule with a greater in-depth look at each of the obligations assigned to the Buyer and the Seller.

The rule of INCOTERM, FCA establishes that the Buyer’s risk is greater than the risk of the Seller if this rule is applied to the contract. According to Wayne & Shippey (2003)[1], the term Free Carrier is used for any mode of transport, including a multi-modal. In Free Carrier, the Seller is the one the clears the goods for export and then is the one who delivers them to the carrier which will be disclosed or specified by the buyer at the named place. If for instance, the buyer’s named place is the Seller’s own premises, then the delivery is completed when the goods have been loaded on the specified means of transport which is to be provided by the buyer. In cases other than this specific circumstance, the delivery is completed when the goods are placed at the carrier’s disposal or another individual nominated by the Buyer on the Seller’s means of transport is ready for unloading.

The rule DAP (Delivered at Place) is the newly added rule in INCOTERM 2010. This rule is used for any transport mode, or it can also be used when there is more than one mode of transport. Under this rule, it is the Seller’s responsibility to arrange for carriage and the delivery of goods ready for unloading from the arriving conveyance at the named place. Under this rule/term, duties are not paid. The Seller’s risk significantly increases when using this term. They bear all the costs and the risk of loss or damage to the goods until they have been delivered on the arriving means of transport, ready to be unloaded at the named place of destination. On the other hand, the Buyer’s risk in this rule is minimized as the Buyer’s obligations include taking the goods at the agreed place of destination.

Lastly, the rule of CIF (Cost, Insurance Freight) differences from the other two mentioned rules as it uses the mode of transportation through maritime. In Cost, Insurance Freight, the Seller is that one that clears the goods for export and is given the responsibility of delivering the goods past the ship’s rail at the port of shipment, it should be noted that this differs from the destination (Wayne & Shippey, 2003)[2]. The categorization of the ‘named port of destination’ in this rule of INCOTERMs is also domestic to the buyer. The norm of payment terms in Cost and Freight transactions mostly includes an advance in cash, open account, and credit letters. This rule’s risks are almost equal for both the Buyer and the Seller, which will be explained by analysing their obligations in a later section. The Seller is to deliver the goods on board the designated vessel. The Seller must also obtain a contract for carriage to the named port of destination and pay the freight and all other costs incurred. Under these terms, the Seller is the one who takes all the risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been delivered on board the vessel at the named port of shipment. Under this rule, the Buyer has the option of agreeing to the scope of insurance with the Seller. However, if no such agreement is made, the Buyer is only necessitated to obtain a minimum cover provided under the Institute of Cargo Clauses.

| Clear for Export | Clear for Import | Contract of Carriage | Point of Delivery | Transfer of Risks | Costs of Carriage | Marine Insurances | Mode of Transport | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCA | SELLER | BUYER | BUYER | First carrier of another person | Point of Delivery | – | – | ALL |

| DAP | SELLER | BUYER | SELLER | Named place of destination | Point of delivery, ready for unloading from the arriving means of transport | – | All | |

| CIF | SELLER | BUYER | SELLER | Named port of shipment | Onboard the vessel | Named port of destination | By Seller only on minimum cover | VESSEL |

Orders completed by our expert writers are

CONTACT US TO GET ACCESS TO THE MISSING INFORMATION.

Table 2-Obligations of Seller under INCOTERMS 2010

It is required under the Ex Works (EXW) rule that Seller is to place the goods at the site which has been issued for disposal of the buyer’s at the named place of delivery. This includes works, factory, warehouse, or at any other place. Even after the goods have been delivered, the Seller must still bear a considerable financial risk as long as the full payment from the Buyer is not made. These specific conditions under the INCOTERMS rules are considerably disadvantageous for the buyer. The Buyer has to arrange everything himself, which includes; export, clearance, transportation, and insurance which results in the Buyer at a higher risk[3]. The Buyer has an obligation to deliver the goods as soon as they are available at the designated place, which may vary by the Seller’s premises or any other place designated by the Buyer. The Buyer is the one that is obligated to bear all the costs and risks involved with organising the transport from the time that it is delivered at the requested premises. The risks of loss or damage to the goods are transferred to the buyer as soon as the goods have been placed in the Buyer’s designated disposal site in the named place of delivery. The Seller is not obligated under this INCOTERMS rule to load the Buyer’s goods on to the collecting vehicle[4]. In certain situations where the Seller is in a better position to load the goods, the FCA (Free Carrier) rule is more appropriate.

Under the Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) rule of INCOTERMS 2010, basically, it is the Seller’s obligation to place the goods at the Buyer’s disposal on the arriving means of transport, which is to be made ready for unloading at the named place of the destination. Under this INCOTERMS rule, it is the Seller that is to bear all the costs and risks of loss or damage to the goods and all the costs incurred through customs formalities, duties, taxes, and all other charges[5]. Therefore, both parties must specify as clearly as possible about the point within the agreed place of destination. This is an important Right of the Seller as he or she bears all the costs and risks up to that point and anything that occurs up to that point, the Seller is accounted for. The Seller should know that the Buyer may only obtain a restricted amount of coverage for the succeeding transportation. It is the Buyer’s obligation under this specific INCOTERMs rule to deliver the goods on the arriving means of transport that should be ready for unloading at the named place of destination[6]. From that specific point in time and onwards, the Buyer is obligated to bear all the costs to the goods’ final destination. The Seller is under no obligation to take out any marine insurance under this rule. It should also be noted that the damage that occurs before the goods reach the named place of destination, but are detected at the final destination can no longer be claimed for from the Seller. Therefore, it is the Buyer’s right to qualitatively and quantitatively examine the goods at the named place of destination. It should also be noted that only restricted coverage can be obtained for the succeeding transport. It is recommended that the parties not use the INCOTERMS DDP rule if the seller cannot directly or indirectly obtain import clearance. If they may arise as an obstacle, the parties should use the DAP rule to be more appropriate.

Under the Free alongside Ship (FAS) rule in INCOTERMS, the Seller is obligated to deliver the goods by placing them alongside the vessel or loading point such as a quay or barge, which needs to be nominated by the Buyer at the named port of shipment. Under this INCOTERMS rule, the Seller is obligated to clear the export goods where they are considered applicable[7]. It should be kept in mind that the Buyer’s right includes the chance to obtain restricted insurance from the named place of shipment. This puts the Seller at risk as they are the ones who bear a considerable financial risk should no payment has been made before the shipments. It is also a risk that the Seller has no guarantee that the Buyer will obtain marine insurance. The Seller’s right where the goods are in a container to hand over the goods to the carrier at a terminal and not alongside the vessel[8]. In these circumstances, the FAS rule is considered inappropriate, so the FCA rule should be used instead. The Buyer’s main obligations under this rule are to deliver the goods when the Seller has delivered them at the named place of shipment. It is also the Buyer’s obligation to contract at their own expense for the carriage of goods from the shipment’s named port. The buyer is at risk of loss or damage to the goods from the time they have been delivered at the named port. It is also ordained under this rule that the Buyer has no obligation to the Seller to make a marine insurance contract.

The contracts of international sale using the INCOTERM 2010 rules are international in nature. Still, they are interpreted under national law or even in an international tribunal when uncertainty arises between the Buyer and the Seller. Under this section, the above-assessed rights and obligations will be assessed using a series of court cases that have evaluated the validity of the mentioned rights and obligations.

An example of a court case that was in breach of the obligations ordained from the ‘Free Alongside Ship’ (FAS) rule in INCOTERMS was the case of Nippon Yusen Kaisha v Ramjiban Serowgee [1938][9] in which the court had held that the appellants which was the Japanese ship owning company (Sellers) were liable to the respondents (Buyers) who were brokers and merchants in Calcutta for the damages representing the value of a certain consignment of jute gunny bags. The Buyers had a special property or right of possession in the goods. The notice of lien and other demands were sufficient to render the Sellers guilty of conversion the notwithstanding the notice of demands in which they delivered the goods under the contract.

Under the Free Carrier rule under INCOTERM 2000; it should be noted that Buyers and Sellers’ obligations have noted changed in the INCOTERM 2010 revision of rules. In the court case of Fleming & Wendeln GmbH & Co v Sanofi SA/AG [2003][10] the “Buyers”; Fleming & Wendeln GMBH & Co challenged an Appeal Award by the GAFTA Board of Appeal as first-tier arbitrators between the Buyers and the Sanofi SA/AG; the “Sellers”. The Buyers of the case had applied for permission to appeal under the Arbitration Act of 1996, section 69[11] in respect to whether in the event the Seller is in breach of successive obligations which includes the failure to deliver goods that are outlined in the contract which integrates the GAFTA default clause. The Buyers had held the Sellers in default and terminated their contract. The question arises if the Buyer is entitled to damages assessed as the difference between the contract price and the market price of the cargo in question by the end of the delivery period. The case surrounds the circumstances that took place on October 15, 1997. The parties mentioned had concluded a contract to sell and purchase 20,000MT-30,000MT at the Sellers’ option Russian/Ukrainian clack sunseed crop. It was held in the contract that the price was to be fixed for each of the shipment latest 15 days prior delivery period under the FCA rule. Deliveries were made under this contract; however, by early 1998, a great deal of the quantity remained undelivered. The court ruled that the board was correct that the Sellers were irrevocably at default, with the result being that the Buyers could resort to the market to buy the undelivered goods. This was the board’s correct method for justification due to clause 28 of the GAFTA[12] clauses.

Under the Delivered Duty Paid obligations of Sellers and Buyers can be seen upheld in the court case, European Commission v Fresh Marine Company A/S [2003][13] in which the court ruled that the Commission community cannot be held liable for any damage other than that which is an adequately direct consequence of the misconduct of the institution. Since the Commission had failed to take necessary measures as soon as the irregularities gave rise to impost on the provisional measures of imports, Fresh Marnine’s products were definitively rectified. Therefore, the court held that the Commission must be held solely responsible for Fresh Marine’s loss of profit starting from the end of January 1998.

Further court cases that appeal to righting the obligations established for Buyers and Sellers under the INCOTERMs rules was seen in the case of Red 12 Trading Ltd [2008][14] in which the court had held that Red 12 was in breach of its own terms and conditions on every occasion that is traded. One of the Buyers; Mr. Singh, was unaware of the meaning of the term “CIF” in which the contract between Red 12 and Mr. Singh stated that it was Mr. Singh that agreed to pay insurance, but instead Red 12 being the “Sellers” the contract appears to have said that Red 12 was responsible for the payment of insurance. The contract’s terms and conditions were also not properly specified at what stage the good would be considered Red 12’s property.

In such cases as the scenario described in a dispute between ProMerc Wholesalers and Bayuern & Co, the Vienna Convention plays a crucial role in imposing the rights and liabilities on both the buyers and the sellers. Under the obligations listed of a seller in the Vienna Convention are delivery of goods, handing over documents related to the goods, and the transfer of property in the goods stated in the contract and assert in the Convention. The Convention has provided s a supplementary set of rules that can be used in the absence of a contractual agreement of when, where, and how the Seller needs to perform their obligations. The Convention outlines the buyer’s general obligations as being to pay for the price of the goods and take the delivery of them according to the contract and the Convention. The Conventions has suggested[15] to buyers and sellers to regulate general issues through their contract by expressing the provision or using trade terms such as INCOTERM. When using such a trade term amends the corresponding provisions of the CISG. Furthermore, the Convention[16] states that if the contract of sale involves that carriage of goods and the seller is not bound to hand them over at a particular place, the risk is passed on to the buyer when the goods are handed over to the first carrier for transmission to the buyer who has been outlined in the contract of sale.

There are other examples as well such as Gas Natural Aprovisionamientos SDG SA v Methane Services Ltd The Gimi [2009][17] in which it was held that the charterer had not given specific orders that had identified the next loading port, the charter party did not require the substitute vessel to be delivered at the place where the previously chartered vessel went off-hire. The court asserted that substitution could only sensibly take place when the cargo had been discharged. By that time the charterer ought to have given orders identifying the next loading port, in which the case used the clause 59 d would have protected it. According to the Halsbury’s Law (2008)[18], charter-party contracts that are affreightment in writing by which the owner of the ship or other vessel lets the whole, or a part of the vessel to a merchant or other person for the conveyance of goods, regarding the consideration of the payment of freight. Furthermore, it highlights the delivery of a vessel into service under this contract, whether the contractor is nonetheless obligated under law to give the order of delivery and vessel destination. Halsbury mentions in this passage the cases Larrinaga Steamship Co Ltd v R [1945][19]& Whistler International Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2001][20].

According to the outlined articles of the Convention, a certain distinction is made between the obligation of the buyer to take delivery and the obligation to take over goods. According to article 60[21], taking delivery is formed by performing all the acts that are reasonably expected of the buyer, which will allow the seller to make the delivery and take over the goods. The Convention clearly covers the obligations of transmitting the goods from seller to buyer; however, it is not clearly defined if this obligation also covers the duty to provide information that is relevant to the productions of the goods or to perform other actions at the earlier stages of actual transmission of goods. Article 60 b[22] of the convention also covers the obligation of the buyer to take over the goods after carriage is arranged by the seller as well as in cases where the contract calls for the seller to make delivery of the goods by placing them at the buyer’s disposal at the seller’s place of business or at any other place that has been defined.

The underlying rationale for constructing the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (Vienna Convention) is to allow its exporters to avoid their choice of issues in law as it offers a substantive set of rules which contracting parties, courts, and arbitrators can rely on unless they have been excluded in press terms of the contract. With such the Convention, articles are thought to include domestic laws regarding a transaction in goods between parties from different contracting companies. The main goal of the Convention was to develop uniform international sales laws. Since its ratification, the treaty is considered the most successful international uniform law as more than eighty countries have ratified the treaty by September 2013. This accounts for a great portion of the world trade, which shows that the Convention successfully aimed. The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) is regarded as a success as the Convention has been accepted by various states from almost every geographical region and stage of economic development, including various states of every legal, social and economic system[23].

The underlying rationale for the construction of the articles, keeping in mind the main purpose of the Convention, which is to maintain uniformity for international sale contracts that can be obliged by international laws that impose rights and liabilities of buyers and sellers under the Vienna Convention is by the use of the principle of favour contracts. When examining the Convention’s article 7, section 2[24], the Convention for all events have disputes interpreted in favour of the contract. For this, the Convention demands cooperation, favourable interpretation and at times, according to circumstance, the original contract’s adaptation (Keller, 2008)[25]. The Convention offers in its article 8[26] three steps for the interpretation of the contract. The rationale that this is based on is the statements and conduct of a party to the contract need to interpret according to the person’s intent. If this fails in terms of intent that it is replaced by the understanding of a reasonable person. Lastly, all the relevant circumstances need to be taken into consideration. The Convention articles clearly define the sale of goods by forming contracts under the treatise’s articles 14 to 24. Within these articles, it is stated that the contract needs to clearly address itself to a person it includes describing the goods, quantity, and price along with indicating the intention for the offeror to be bound on acceptance[27]. Furthermore, to maintain uniformity regarding the statutes that govern the contracts and obligations of Buyers and Sellers, the CISG does not recognise common law unilateral contracts. Additionally, any remedies of the buyer and seller in terms of breach of contract depend on the breach’s character. This was viewed in the case Hadley v Baxendale [1854][28] in which the test of foreseeability was used in a broader sense which made it more generous towards the aggrieved party. It was seen in this case that the breach was not fundamental, in which the contract could not be avoided, and remedies were sought, which included the claiming of damages. Furthermore, if the breach of contract is not fundamental claims can also be made regarding specific performance that was desired and adjustment of price.

One of the most commonly used ways for Sellers’ trade finance is through documentary credit, which is currently governed under URC 522 rules. This mainly relies on commercial letters of credit. The issuing bank states its commitment to pay the Seller (beneficiary) a set amount of money on behalf of the Buyer as long as the Seller complies with the given terms and conditions in the sale contract (Contessi &Nicola, 2012)[29]. This financial instrument allows the Buyer to use his cash flow for other purposes rather than paying the Seller in a specific period of time. This also makes sure that the Seller will be paid their dues in a timely fashion. This financial instrument is suited for international contracts that are more difficult to enforce and have a higher risk than each party’s domestic contracts due to the foreign party’s creditworthiness is difficult to evaluate (Contessi &Nicola, 2012)[30].

Another trade finance method is the reliance on the letter of credit, currently governed under UCP 600 rules. With this method, the bank or financial institution undertakes or promises on behalf of the Buyer to the Seller, that if the Seller presents the complying documents to the Buyer’s nominated Bank or Financial institution which has been already specified by the Buyer in the Purchase Agreement, then the Buyer’s Bank or financial institution will make payment to the Seller. There are several documents that the Seller can present to receive payment. Commonly, the Seller usually presented documents that prove the goods were sent. It is most common by the Seller to present the original Bill of Lading (BOL) which is normally accepted by banks as proof that the goods have been supplied (Contessi &Nicola, 2012)[31]. However, the form of documentation is open to negotiation by the Seller and Buyer. It may even contain certain requirements to present documents issued by a neutral third party who provide evidence to the quality of the goods shipped, place, or their place of origin. In such contracts it is common to include that the following documents be presented for Seller t receive payment from the Buyer’s bank:

One of the regulatory issues on the letter of credit is that the payment obligation is independent of the underlying contract of sale or any other contract that has been erected in the transaction (Auboin, 2010)[32]. Therefore, the bank’s or financial institution’s obligation and responsibilities are defined only by the terms placed in the credit letter. The sale’s contract is of no concern to the bank and does not affect its liability; this has been ordained under the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP)[33]. Furthermore, under UCP[34], the bank only deals with the documents and hare not concerned with the goods. Thus, if the documents that are tendered by the Seller or their agent are in order and fit the requirements under the contract, then the bank is obliged to pay without further qualifications (Auboin, 2010)[35].

The main differences between letters of credit (LC) and documentary credit (DC) are that under LC the guarantee of payment is made by at least one bank that is acceptable to both the Seller and the Buyer[36]. Also, there is a time limit for shipment within the LC; it further stipulates is partial or scheduled shipments are required. Also, the cost of LCs is variable, which depends on factors such as importing country risk; the cost is also substantially higher than DC. On the other hand, documentary credit is controlled through the banking system parallel to URC 522 rules. There is also no guarantee of payment made by any bank. Also, there is no time limit under DC; however, if the contractual requirements relating to time are not met, the Buyer is unlikely to pay. Furthermore, the URC rules relating to partial and scheduled shipments are not restricted, but contractual responsibilities need to be obliged by. The cost of DC is commonly fixed and is lower than that of LC.

Trade finance, traditionally speaking, always seems to have received preferred treatment from national and international regulators and international financial institutions and agencies in the treatment of trade finance claims, as it is often seen as the safest, collateralized, and self liquidated form of trade finance. According to Auboin (2010)[37], the preference for trade finance is a reflection of the systematic importance of trade, especially trade lines credit as it allows for this type of credit to be restored and trade to flow again. The regulatory issue mostly arises with documentary credit from Basel II regulation as this regulation is designed and implemented so that when banking is being retrenched, it seems to affect the supply and trade credit more than the other forms of lending that are more potentially risky. This regulatory premise became a lot of trade credit issues under Basel II during the collapse of trade between late 2008 and early 2009. Later on, in April 2009, the issue came up in the G-20 Leaders in London, which called on regulators to exercise a bit more leniency in applying the Basel II rules to support trade finance.

One of the issues that are greatly faced with the trade finance instrument of documentary credit is it often struggles with compiling with the Basel II rules of regulation. The main reason that regulation has impacted this form of trade finance is that many banking regulators do not understand the methods of trade and trade finance operation in practice[38]. This results in much of the banking community being unable to explain a documentary credit to regulators and provide evidence to these regulators about is the high level of safety and logicalness of the activity. Many of the regulatory issues in the crossfire of documentary credit are; pro-cyclicality, the disproportionate capital requirement for trade finance in crisis period; and rigidity in maturity cycle to short-term lending[39][40]. Much of the regulatory community is complaining about the lack of historical and performance data to validate the risk attributes. This impacts the banks, as many banks face difficulty identifying and isolating adequate data to produce valid estimates of risk attributes for trade lending which further impacts international trading companies of not having a safe lending option for their payment or cash flow.

[1] Wayne, J and Shippey, K.C. (2003) ‘A Short Course in International Contracts’, World Trade Press, pp. 47

[2] Wayne, J and Shippey, K.C. (2003) ‘A Short Course in International Contracts’, World Trade Press, pp. 46

[3] Zurich. (, 2011). INCOTERMS 2010- Domestic and International Trade Terms, English Version, pp. 4

[4] Zurich. (, 2011). INCOTERMS 2010- Domestic and International Trade Terms, English Version, pp. 4

[5] Franco Ferrari. (, 2005). ‘What Sources of Laws for Contracts for the International Sale of Goods? Why One has to Look Beyond the CISG’, International Review of Law and Economics, 25, pp 8

[6] Franco Ferrari. (, 2005). ‘What Sources of Laws for Contracts for the International Sale of Goods? Why One has to Look Beyond the CISG’, International Review of Law and Economics, 25, pp 6

[7] Franco Ferrari. (, 2005). ‘What Sources of Laws for Contracts for the International Sale of Goods? Why One has to Look Beyond the CISG’, International Review of Law and Economics, 25, pp 7

[8] Franco Ferrari. (, 2005). ‘What Sources of Laws for Contracts for the International Sale of Goods? Why One has to Look Beyond the CISG’, International Review of Law and Economics, 25, pp 7

[9] Nippon Yusen Kaisha v Ramjiban Serowgee [1938] AC 429, [1938] 2 All ER 285

[10] Fleming & Wendeln GmbH & Co v Sanofi SA/AG[2003] EWHC 561 (Comm)

[11] Arbitration Act 1996, s 69.

[12] The Grain and Feed Trade Association, rule 28

[13] European Commission v Fresh Marine Company A/S (Case C-472/00 P) – [2003] All ER (D) 180

[14] V20900: Red 12 Trading Ltd, LNB News (02/01/2009) 129

[15] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.3

[16] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.67

[17] Gas Natural Aprovisionamientos SDG SA v Methane Services Ltd The Gimi [2009] EWHC 2298 (Comm)

[18] Halsbury’s Laws (5th ed.). (2008), pp. 241-242.

[19] Larrinaga Steamship Co Ltd v R [1945] 1 All ER 329, [1945] AC 246, HL

[20] Whistler International Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2001] 1 All ER (Comm) 76, [2001] 1 AC 638, [2000] 3 LR 1954,HL.

[21] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.60

[22] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.60(b)

[23] Felemegas, J. (2000). ‘The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods: Article 7 and Uniform Interpretation. Pace Review of the Conventional on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), pp. 115.

[24] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.8

[25] Keller, B. (2008). ‘Favor Contractus reading the CISG in Favor of the Contract’, pp.249 para.3

[26] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art.7, s.2

[27] United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, art. 14.

[28] Hadley v Baxendale [1854] 9 Exch 341

[29] Contessi, S. & Nicola, F. (2012). “The Role of Financing in International Trade during Good Times and Bad’.The Regional Economist, pp. 3-6.

[30] Contessi, S. & Nicola, F. (2012). “The Role of Financing in International Trade during Good Times and Bad’.The Regional Economist, pp. 7-9

[31] Contessi, S. & Nicola, F. (2012). “The Role of Financing in International Trade during Good Times and Bad’.The Regional Economist, pp. 15-16

[32] Auboin, M. (2010). ‘International Regulation and Treatment of Trade Finance: What are the Issues?’ World Trade Organization, pp. 13-15

[33] UCP, article 4(a)

[34] UCP, article 5

[35] Auboin, M. (2010). ‘International Regulation and Treatment of Trade Finance: What are the Issues?’ World Trade Organization, pp. 15

[36] Bank Millennium. (2013). Documentary letter of credit. Trade Finance, para. 5

[37] Auboin, M. (2010). ‘International Regulation and Treatment of Trade Finance: What are the Issues?’ World Trade Organization

[38] International Chamber of Commerce, ‘ICC calls on G20 to Address Impact of Basel II on Trade Finance’ (ICC, 27 March 2009)

[39] International Chamber of Commerce, ‘Banking Commission Recommendations on the Impact of Basel II on Trade Finance’(ICC, 2009) Document 470/1119

[40] Chor, D & Manova, K. (2010) ‘Off the Cliff and Back? Credit Conditions and International Trade during the Global Financial Crisis’. Working Paper No. 16174, NBER

If you are the original writer of this assignment and no longer wish to have the paper published on www.ResearchProspect.com then please:

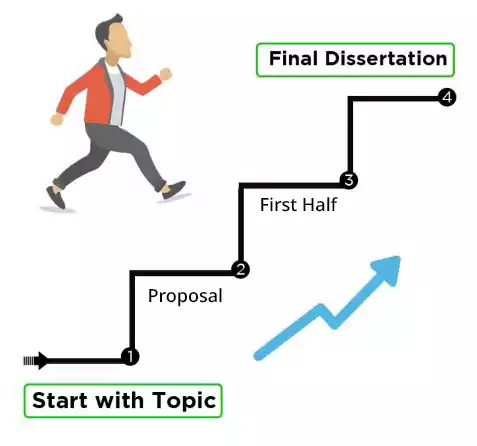

The core steps to write a PhD assignment: